Antoine Vestier

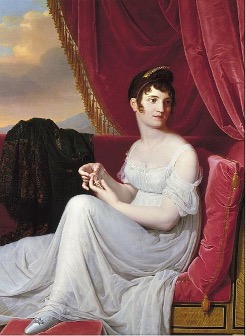

Portrait of Mme. Delahaye, three-quarter-length, in a white décolleté dress

Provenance:

With A. J. Seligmann, Paris, by 1937.

Collection of Lady Sassoon (c. 1864-1955).

Sale, Christie’s, London, 8 June 2021, lot 230, when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

Anne-Marie Passez, Antoine Vestier, 1740-1824, Paris, 1989, no. 115, p. 228 (illustrated p. 229).

Catalogue Entry

The figure of a charming woman sitting on an armchair dominates the present portrait. The seat, embellished by wooden arms in the shape of griffins, along with the section of a table and the curtain visible on the left, suggest an elegantly furnished interior. The sitter holds a small book in her right hand. She has just interrupted her reading to look confidently outside the canvas, straight at the viewer. With her other hand, she holds the skirt of her long white satin décolleté dress, which is belted right under the bust with a blue sash. The woman wears her raven black hair elegantly coiffed, with black curls adorning her forehead. Her outfit is not embellished by any jewellery if not a pair of sober, gilded earrings with a dark, teardrop stone.

Fig. 1. François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter (1770–1841), A pair of empire mahogany and mahogany-veneered fauteuils, circa 1805, Private collection.

A signature annotated near the chair’s arm, reading ‘Vestier,’ reveals the painting’s author. Born in Avallon, Burgundy, in 1740, Antoine Vestier (1740-1824) moved to Paris in 1760 to start off his career as a miniature painter, soon becoming a pupil of enameller Antoine Révérand. Marrying Révérand’s daughter in 1764, he was registered the same year as a student at the Paris Académie Royale. Following a trip to England in 1776, when he became acquainted with the leading English portraitists of the period, Vestier devoted himself to portraiture, working primarily for the French aristocracy. He evolved a style close to that of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805) and Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802), whose support was decisive for Vestier to become a full member of the Académie in 1786. With the advent of the French Revolution and the growing popularity of Jacques-Louis David, Vestier’s style underwent significant changes, favouring simpler compositions and placing more emphasis on his sitters’ character. In 1798, he painted two of his most exquisite portraits, the Portrait de Jean Theurel (Musée des Beaux Arts, Bodeaux) and the Portrait de Jean Henri Latude (Musée Carnavalet, Paris). Although Vestier’s popularity declined after the 1790s, he continued receiving commissions, and exhibiting oil portraits and miniatures at the Salon until 1806.1

Fig. 2. François Gérard, Portrait de Juliette Récamier, oil on canvas, 257 x 183 cm., c. 1805, Musée Carnevalet, Paris.

In the monographic volume Antoine Vestier, 1740-1824, Anne-Marie Passez writes that elements in the Portrait of Mme. Delahaye, such as the armchair, the woman’s coiffure and her dress, suggest the work was probably made between 1804 and 1806.2 The griffin heads adorning the armchair exemplify the profusion of zoomorphic elements that characterised French Neoclassical furniture. In particular, the present armchair bears close similarities to the creations of Georges Jacob (1739–1814), the most prominent Parisian chair-maker during the reign of Louis XVI. It might in fact be one of his fauteuils meublants, formal chairs with straight backs usually decorated with motifs of animals and fantastic creatures, including sphinxes, swans and griffins, deriving from a fascination with classical antiquity, which became popular in France at the very beginning of the nineteenth century (ex. Fig. 1). A classical aesthetic informed the arts, the costume and the fashion of the time. It was fashionable for women of affluence to have their hair pulled back in chignons, adorned with wreaths, jewellery and tiaras – as in the present painting – with curls carefully arranged on the forehead and in front of the ears using huile antique, an extremely expensive scented oil. Such a hairstyle, known as coiffure à la Titus, was inspired by portrait busts of the Roman Emperor Titus and became popular in France among both men and women. The sitter’s dress further supports the dating of the portrait to the first years of the nineteenth century. The white gown, evocative of the classical world, is a garment that came into vogue during the Directory and became the height of Empire fashion. Designed on what was believed to be ancient Greek dress, it consisted of a long gown made of thin, flowing material, gathered with a narrow ribbon under the breasts and falling loosely below. Similar dresses à la grecque appear in famous portraits of the period, including the sensuous Portrait de Juliette Récamier (Fig. 2), painted by Gérard in 1805, Ingres’ Portrait de Madame Rivière (Fig. 3) from 1806 and Bernard Dudivier’s Portrait de Thérésa Tallien (Fig. 4) from the same year. The garments worn by these women all share an Empire silhouette, with its distinctive Empire waist and typically short sleeves (Fig. 5-6).3

Fig. 3. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait de Madame Rivière, oil on canvas, 117 x 143 cm., Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Fig. 4. Bernard Dudivier, Portrait de Thérésa Tallien, oil on canvas, 125.5 x 93.3 cm., 1806, The Brooklyn Museum, New York.

The woman portrayed in the present work has been identified as Mme. Delahaye according to a plaque on the painting’s original frame. Although the lack of archival information prevents us from knowing the personal history of the woman, she is depicted according to the conventions of early nineteenth-century élite female portraiture. As was customary at the time, Vestier underlined the noble simplicity, dignity and timelessness of the portrayed by adopting a classicizing aesthetic. The painting’s style echoes such a vision through its clarity of contours, splendid craftsmanship, simplicity of composition and balance. Vestier has immortalized the image of a glowing woman, whose alabaster skin draws her closer to a marble statue of a goddess rather than to a real woman. Yet, her sympathetic expression, along with her interrupted reading, bring her back to the ordinariness and intimacy of daily life. Vestier’s fascination for Jacques-Louis David, whose style greatly influenced the artist’s late production, is suggested by the sitter’s head turned to confront the viewer and the depiction of her upper section as in relief against a monochrome background.

Fig. 6. Evening dress, French, 1804-1805, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Gifts in memory of Elizabeth N. Lawrence, 1983.

Fig. 5. Dress, cotton and linen, 1800-1805, Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the Jason and Peggy Westerfield Collection, 1969.

Books had appeared in Vestier’s female portraits since the late 1780s, as exemplified by his famous Portrait of a Lady with a Book by a Fountain (Fig.7). The depiction of a young woman accompanied by a book attested to her good manners, education and demure femininity.4 The motif of reading, or interrupted reading, within the private space of the sitter’s home was a device for artists to display not only her moral attributes, but also her imaginative and intellectual life. The present book is most certainly a novel, a secular literary genre that gained extreme popularity in France over the course of the nineteenth century. When the portrait was executed, privately educated women such as Mme Delahaye were the major consumers of an élite market that would later expand to other strata of society, from the upper bourgeoisie to the middle class. They were avid readers, who often took up the pen themselves, and fuelled debates on literary novelties in their correspondence and salons, paving the way for women of the following generation to participate in cultural and political debates beyond the domestic household.5

Fig. 7. Antoine Vestier, Portrait of a Lady with a Book by a Fountain, oil on canvas, 130.5 x 98.5 cm., 1785, MASP – Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, São Paulo.

The Portrait of Mme. Delahaye comes from the important collection of Lady Leontine Sassoon (c. 1864–1955). Born Levy in Cairo, Egypt, Leontine married businessman Sir Edward Elias Sassoon, 2nd Baronet of Bombay (1853–1924). Elias was involved in growing the Sassoon family trading business – the David Sassoon & Co. – in Bombay, India, and in expanding it into China, founding new branches in cities including Hong Kong and Shanghai. Due to their immense wealth and their movement through the continent of Asia, Elias and his wife came to be known as the ‘Rothschilds of the East.’ Lady Sassoon, who resided at 19 Belgrave Square in London and Keythorpe in Bournemouth, was a passionate collector of Old Master paintings, English and French furniture, clocks and objets d’art. Among the masterpieces of her collection were eight canvases by Flemish artist Pieter Casteels III (1684-1749).

1 For a brief biography of Antoine Vestier, see Katharine Baetjer, French Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Early Eighteenth Century through the Revolution, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019), p. 296. 2 A. M. Passez, Antoine Vestier, 1740-1824, (Paris, 1989), p. 228: «La robe et la coiffure typiquement Empire, comme le fauteuil à tête de griffons, situent la peinture entre 1804 et 1806». 3 For information on women’s fashion at the turn of the nineteenth century, see E. Claire Cage, ‘The Sartorial Self. Neoclassical Fashion and Gender Identity in France, 1797-1804,’ in Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 42, No. 2 (Winter, 2009), pp. 193-215. 4 For a detailed study on the topic, see Kathryn Brown, Women Readers in French Painting, 1870-1890: A Space for Imagination, (London: Routledge, 2016). 5 For a study on the history of the novel and its audience in France, see, Martyn Lyons, Readers and Society in 19th Century France: Workers, Women and Peasants (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001); Kate Flint, The Woman Reader, 1837-1914, (New York: Oxford UP, 1993).

Condition:

The painting has recently been cleaned. It is in overall good condition.