Antoine Vestier

Portrait d’Adélaïde-Geneviève de la Croix, marquise d’Hozier, tenant une partition

Provenance:

Collection of the Marquis Denis-Louis d’Hozier, thence by descent to his wife, Adélaïde-Geneviève de la Croix († 1803).

Thence by descent to her son Ambroise Louis Marie († 1846).

Thence by descent to the Comtesse de Labriffe, born d’Hozier.

Thence by descent to Solange de Labriffe, Duchesse d’Ayen.

Thence by bequest to her sister, the Duchesse de Dalmatie.

Thence by gift in 1977, collection of the Marquis de Vassart d’Hozier.

Sale, Blanchet & Associes, Paris, 28 June 2019, lot 35, when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

Anne-Marie Passez, Antoine Vestier, 1740-1824, Paris, 1989, p. 23, 104, 110, cat. 18 (illustrated p. 111).

Catalogue Entry

Fig. 1. Antoine Vestier, Portrait de Denis Louis, marquis d’Hozier, Président de la Cour des Comptes de Normandie (1720-1788), oil on canvas, 81 x 64,7 cm., Private collection.

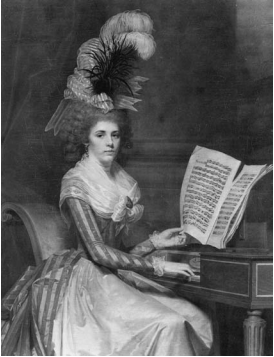

Set against a monochromatic background, the charming figure of a woman is captured while sitting on a chair as she points to a music sheet she holds in her hand. She looks confidently at the viewer, wearing a pink silk dress trimmed with marten and lace at the wrists, and has her hair elegantly coiffed, a distinctive marker of high birth and status. The woman is indeed Adélaïde-Geneviève de la Croix, marquise d’Hozier. Born into the aristocratic French family of the de la Croix, which traced its origins to the twelfth century, she entered the illustrious d’Hozier family after marrying the marquis Denis-Louis d’Hozier (1720-1788), Advisor to the King in all his Councils and President of the Normandy Court of Accounts, in 1764. Although the exact circumstances of the execution of the present work remain unknown, it was probably commissioned by the woman’s husband. The portrait is indeed documented in the collection of Denis-Louis d’Hozier, before being inherited by Adélaïde-Geneviève and, at her death in 1803, by her son Ambroise-Louis Marie. The painting exceptionally remained with the d’Hozier family for generations, until it was sold at auction in 2019.

Fig. 2. Joseph Ducreux, La Princesse de Lamballe, Marie-Thérèse-Louise de Savoie-Carignan, oil on canvas, 123 x 93.6 cm., 1778, Château de Versailles, Versailles.

A signature annotated on the music sheet reveals the name of the portrait’s author: ‘Vestier fecit.’ It is the distinctive signature of French painter Antoine Vestier, reappearing in several of his portraits. Born in Avallon, Burgundy, in 1740, Vestier started off his career as a painter of pastel and miniature portraits. In 1781, he was registered as a student at the Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, where he was admitted as a full member in 1786 with the support of painter Joseph-Siffred Duplessis (1725–1802). From the later 1760s through the early years of the nineteenth century, Vestier signed and dated numerous fine miniatures, and built a practice as a portraitist, working primarily for the French aristocracy. By the time he executed the present painting, Vestier had become the official portraitist of the d’Hoziers, portraying six members of the family – including Adélaïde-Geneviève – from 1766 onwards. The artist painted a portrait of the Marquis Denis-Louis (Fig. 1), of his brothers Antoine-Marie, Charles-Pierre and Jean-Francois (known as the “chevalier d’Hozier”), as well as of his sister and sister-in-law.

Fig. 3. François-Hubert Drouais (attributed), Portrait de la Princesse Louise-Marie de France, 225.2 x 146.3 cm., oil on canvas, ca. 1770, Château de Versailles, Versailles.

In comparison with the other five paintings of the series, the Portrait d’Adélaïde-Geneviève de la Croix seems to have been executed later, possibly at some point in the mid-1770s. Certain details of the costume, such as the shape of the sleeves, and, particularly, the woman’s hairstyle match the fashion of the reign of Louis XVI. The marquise wears her hair up, according to the so-called pouf hairstyle, a voluminous coiffure constructed in height using pads and cushions, usually shaped like a heart, and a mixture of real and ‘pomaded’ false hair, which were eventually powdered with grey or white powder. In sober versions of poufs, hair would be curled symmetrically on the sides, as can be seen in the present work. The relative simplicity of the marquise’s version of the pouf and the lack of particular ornamentation might testify the debut of this type of coiffure, which was originally introduced at the court of Louis XVI in 1774. In the years to come, poufs would become increasingly more decorative and extravagant, as exemplified by many portraits of noblewomen, such as Marie Thérèse Louise de Savoie (Fig. 2) and, primarily, queen Marie-Antoinette.

Fig. 4. Antoine Vestier, Portrait de Pascale Hosten, Comtesse d’Arjuzon, oil on canvas, ca. 1790, Private collection, Paris.

Elegance must have been one of the prerogatives of the Marquise d’Adélaïde-Geneviève de la Croix. The woman was updated on the latest trends not only in hairstyle, but also in fashion. Her dress is a robe à la francaise, or sack-back gown, which by the 1770s had become the second most elegant outfit in France after court dress. In front, the gown featured a tight-fitting bodice with a square neckline, usually adorned by decorations such as ruffles, ribbon bows and flowers, as in this case. Tight sleeves covered the arm from the shoulders to the elbows, where many layers of lace, called engageantes, circled the lower arm, as shown in the present work. Details of ultimate sophistication are the ribbon bow encircling the marquise’s neck, perfectly matching the rest of the outfit, and the luxurious marten trimmings of her dress. A similar ornamentation embellishes, for example, one of the dresses of princess Louise-Marie de France, one of king Louis XV’s daughters, as shown in a portrait by Francois-Hubert Drouais (Fig. 3). The beauty of the marquise’s outfit is further reinforced by the masterful way it was painted by Vestier, the softness of fur, the smoothness of silk and the intricacies of lace appearing as almost palpable to the touch.

Fig. 5. Antoine Vestier, The Singer Rose Renaut (La Cantante Rose Renaut), oil on canvas, 81.3 x 66 cm., 1791. © Phoenix Art Museum. All rights reserved.

Vestier’s skills as a painter are also revealed by the attention he paid to depicting the woman’s hands, one of which points to a music sheet. It is a vocal score with harpsichord accompaniment. Throughout his career, Vestier painted many of his models, including singers and musicians, accompanied by a large variety of instruments. Several of his female subjects are depicted at the harpsicord or, from the 1780s, at the more modern piano carré (Fig. 4). The present work can be closely compared to another portrait by the artist depicting the singer Rose Renaut, today in the Phoenix Art Museum (Fig. 5). Alike Adélaïde-Geneviève, the woman diverts her attention from a music sheet and confidently engages with the viewer through her gaze. The harpsichord, clearly visible on the left, does not appear in the present portrait. It is ideally located outside the canvas. By creating a dialogue between the space of the beholder and that of the portrayed individual, Vestier has succeeded in giving a concrete sense of the sitter’s now lost world. The viewer will always be waiting for the marquise d’Hozier to start singing.

Condition:

The painting is in extremely good condition. It is original in size and its canvas is unlined. No major damages, repairs or losses of colour are visible. The surface has recently been cleaned.

Considering that the painting remained within the d’Hozier family for generations, the frame could be assumed to be original to the work.