William Etty

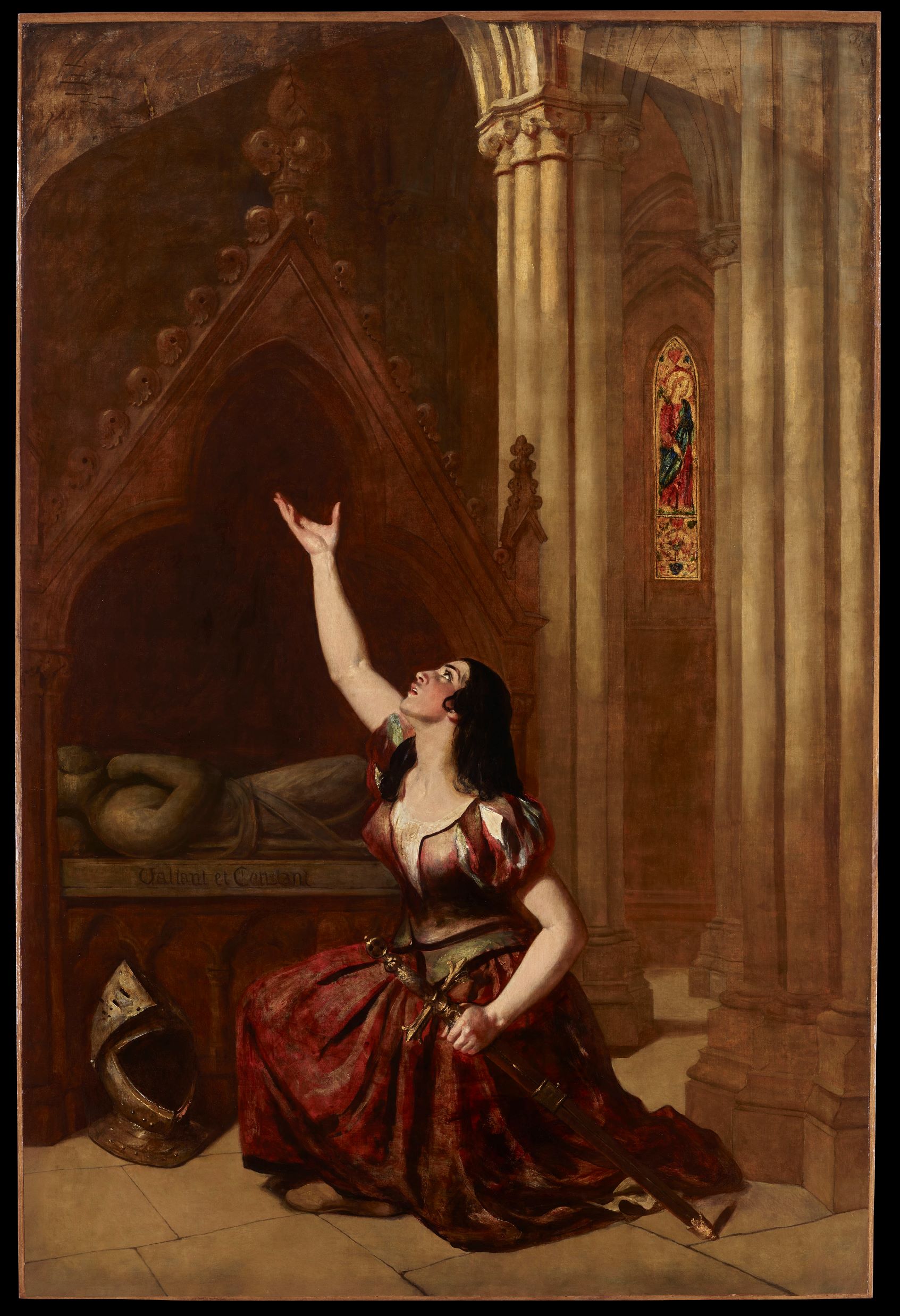

Joan of Arc, on finding the sword she had dreamt of, in the church of St. Catherine de Fierbois, devotes herself and it to the service of God and her country

Provenance:

Jointly purchased from the artist by Richard Colls, William Wethered and Charles W. Wass for £2.500, 1847.

Sale, William Wethered, 8 March 1856, lot 150 (as Joan of Arc finding the sword).

Sale, William Wethered, 27 February, 1858, lot 109.

Charles Read (possibly).

Sale, 18 May 1885, lot 244 (as Joan of Arc), bought by Bolton for 20 guineas.

Sale, H. S. Ashbee, 19 November 1900, lot 85 (as Joan of Arc at the Tomb of Saint Denis), bought by Maple for 14 guineas.

Llantarnum Abbey, Cwmbran, South Wales.

Private collection.

Sale, Bonhams, London, 22 September 2021, lot 15, when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

C. R. Leslie, “Lecture on the Works of the Late William Etty, Esq. R.A., by Professor Leslie,” in Athenaeum, (March 30, 1850), pp. 349-352.

A. Gilchrist, Life of William Etty, London 1855, pp. 53, 107, 172, 224-225, 228, 234-235, 259, 341.

D. Farr, William Etty, London 1958, pp. 98-108.

Catalogue Entry

William Etty was one of the last English academic history painters and the greatest figure painter of the Romantic school in England. Born in York in 1789, he moved to London in 1805 after completing a seven-year apprenticeship with printer Rober Peck. One year later, he entered the Royal Academy schools and trained with Thomas Lawrence from 1807 to 1808. In 1811, Etty started exhibiting at the Royal Academy with regularity, becoming widely respected for his use of colour and ability to produce realistic flesh tones. In 1820, he presented his first substantial painting to the Academy, The Coral Finder, followed in 1821 by The Triumph of Cleopatra. From 1822 to 1823, Etty travelled across Europe, doing a Grand Tour that led him to visit the Low Countries, France and Italy, where he spent nine months residing in Venice. Following his return to London, he was elected a Royal Academician, defeating Constable by eighteen votes to five. Etty became one of the few British painters to make a career out of history painting, a genre that allowed him to explore the nude to the fullest. During the 1830s and 1840s, he focused on less ambitious and smaller works, such as portraits and landscapes. Etty died in York in 1849, after the Society of Arts honoured him with a major retrospective bringing together 133 of his paintings.1

Fig. 1. William Etty, Joan of Arc on horseback at the gates of Orléans, oil on canvas, 305 x 460 cm., Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans, Orléans.

Etty executed the present work during the last phase of his career.2 The painting is dedicated to Joan of Arc (1412-1431), the French heroine who played a crucial role in the final phase of the Anglo-French Hundred Years’ War. It depicts a miraculous event happening at the beginning of 1429. The young “Joan the Maiden,” as she was known, was on her way to Orléans to face the British army that sieged the city. While in Tour, voices told her that the ancient sword of Charles Martel was buried behind the main altar of the church of St. Catherine in Fierbois, a small village in the central Loire. Once it was found, the sword became Joan’s weapon and the symbol of her coat of arms. Although, according to the legend, Joan did not find the sword herself, Etty painted her inside the church of St. Catherine, kneeling in profile before the altar hosting the tomb of a “valiant and loyal” knight. As per the artist, “I suppose her to have found the sword she had seen in her dream, and invoking the inspiration from heaven which sustained her through her arduous course.”3 Etty depicted the heroine wearing secular clothes – a red and green dress with a white undershirt and short puffed sleeves – and with raven black hair falling down her shoulders. The helmet at her feet forecasts her future role as a commander. Joan raises her bare right arm straight towards the sky, as she holds the sword in her other hand, looking upwards in rapture, promising her loyalty to God in fighting for her country. According to a letter dated 23 November 1845, Joan’s face was modelled on that of a young lady called Betsy, whom Etty met at Westminster Abbey and who repeatedly sat for him with her father’s permission.

Fig. 2. William Etty, Study for the martyrdom of Joan of Arc, pen, 11.2 x 18.4 cm.

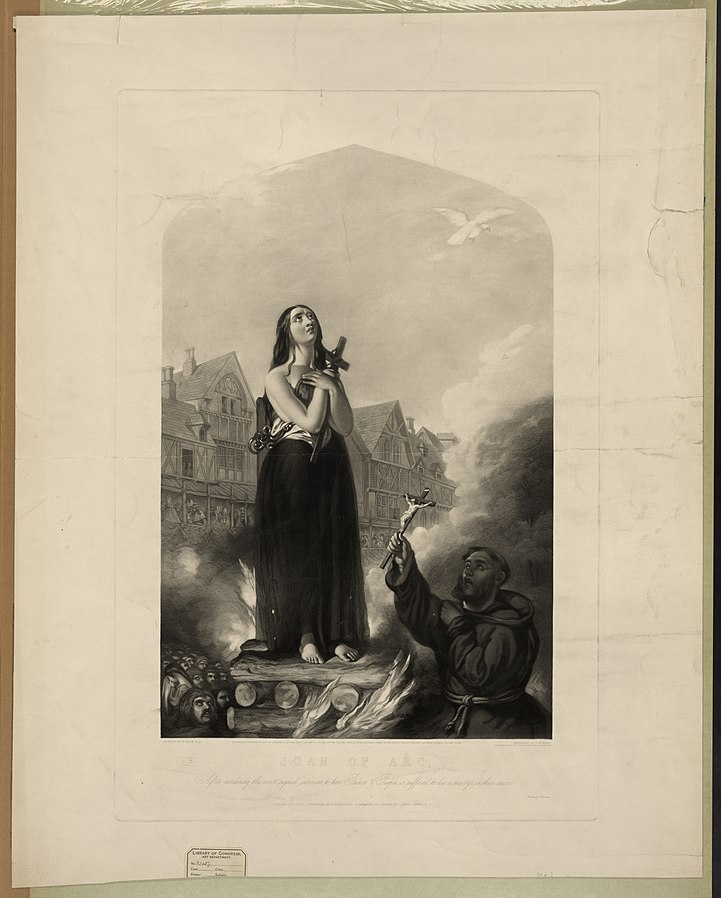

Joan of Arc originally belonged to a group of three monumental canvases that Etty executed in 1847 for the Royal Academy exhibition.4 The large triptych illustrated three key moments in the life of Joan of Arc, showing her triple role of saint, patriot and martyr. In the RA catalogue, the present work is described as “123 left Joan of Arc, on finding the sword she had dreamt of in the church of St. Catherine de Fierbois, devotes herself and it to the service of God and her country.” The central canvas, described as “124 centre Joan of Arc makes a sortie from the gates of Orleans, and scatters the enemies of France” is today in the Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans (Fig. 1). The third painting, “125 right Joan of Arc after rendering the most signal services to her Prince and people, is suffered to die a martyr in their cause,” is now lost. An initial sketch of the work survives (Fig. 2), while the original composition is known from contemporary prints (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Charles Wentworth Wass after William Etty, print, 1851.

The idea of the tryptic had come to Etty years earlier, when, in 1839, he had visited Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey. As the artist recalled, “hearing the anthem sung, and looking towards the Grand Portal, I seemed to see her, in imagination, riding the Gates of Orléans, and carrying the Siege thereof.”5 The artist was to be haunted by this vision of Joan of Arc, and, by September of that year, he had already designed the triptych in pen and ink. Etty thought of Joan as “the Judith of modern times”6 and conceived the picture in the form of an epic, with a beginning, a middle and an end. The multiple of three seems to have been a recurring element in Etty’s oeuvre, as attested, for instance, by his Judith and Holofernes (Fig. 4). As the artist himself wrote, this triptych, that of the Joan of Arc, The Combat (1825, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh), Ulyses and the Syrens (1837, Manchester Art Gallery) and Beniah (1829, York Art Gallery) “make nine colossal pictures, as it was my desire to paint three times three.”7 All paintings in this group are imbued with moral themes and some, including the present one, convey ideas of patriotism and devotion to one’s people and to God. This cycle shows how Etty was trying to emulate the heroic history pictures of the French Romantics, including Delacroix and Gericault. It epitomises how he followed in the footsteps of Reynolds in continuing the path to create an English school of history painting as there was in many parts of Europe at the time.

Fig. 4. William Etty, Study for the Judith and Olofernes triptych, oil on canvas, 54 x 73.7 cm., Private collection. The original work is in the collections of the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

In 1843, Etty embarked on a journey to visit the places connected with the life of Joan of Arc. On August 16, he left London for France, travelling with his friend John Wood to Rouen, Paris, Saint Denis and Orléans. This “pilgrimage” fuelled Etty’s imagination: he prepared many sketches as he “saw all the pictures related to her that had been done in modern times” and set his thought on completing his last great work. As Etty said, “it was something to know you were on the spot where this Heroine trod, and exerted herself in the cause of her country.”8 Nevertheless, it was not until a few years later, in 1846, that Etty started to seriously work on the tryptic with the aim of exhibiting it the following year. The artist was experiencing a chronic respiratory illness, yet he eventually succeeded in his intent, “fighting side by side by my inspiring Heroine.”

Fig. 5. Charles Wentworth Wass after William Etty, engraving, 73.4 x 44.3 cm., 1851, York Art Gallery, York.

As documented by Samuel Phillip’s in the review of the 1847 Royal Academy exhibition he wrote for The Times, the Joan of Arc triptych was exhibited in the great room, instantly catching the visitors’ attention.9 Although the piece received mixed reviews, Etty’s biographer Alexander Gilchrist stated that praise was received by “lovers of Art, and brother Artists alike, including Turner, Landseer and Leslie, among others.” The Literary Gazette noted that it was “we think, the largest piece we ever saw in the Royal Academy” and that “in the first compartment, the heroine wants dignity of person and countenance.” In reviewing the painting, the Art Union found that the “countenance shows much fervour and enthusiasm, without anything like theatrical extravagance.” The London Magazine commented that “the sad episode of heroism [was] wonderfully told; the seizure of the sword is powerfully conceived; the grandeur of the sortie, and the devotedness of the heroine, as her charger gallops over the vanquished and slain foe; and the fervour of the dying heroine are all impressive beyond description. There may be defects of drawings in various points of the composition, but the colouring, especially of the flesh, is masterly; and there is a barbaric picturesqueness in the triple scene, which is a startling novelty in British art.”

Within ten days after the triptych was presented at the RA, C. W. Wass and Richard Colls purchased it at the huge sum of 2.500 guineas. Etty put the finishing touches to the pictures in August, when the works were on show at Coll’s premises in Bond Street. Wass undertook to engrave the three paintings (Fig. 5) and planned to tour them around the country. Eventually, only a few prints of the engravings were produced and the tour never happened. After Wass declared himself bankrupt in 1852, the three paintings were separated and sold. By the 1950s, they were all believed lost or destroyed. After passing through the sale rooms several times, the present canvas ended up in the collection of Llantarnam Abbey, Cwmbran, in South Wales.

1 For detailed biographical information on William Etty, see Alexander Gilchrist, Life of William Etty (London, 1855). 2 For a study of Etty’s latest production see, C. R Leslie, “Lecture on the Works of the Late William Etty,” in Athenaeum (March 30, 1850), pp. 349-352. 3 Ibid. 4 London, Royal Academy, 1847, no. 123, no. 124 and no. 125. 5 William Etty, “Autobiography of William Etty, R.A.”, in The Art‐Journal (1 February 1849): 40. 6 William Etty, letter published in The Fine Arts Journal. 7 Etty, “Autobiography of William Etty, R.A.” 8 C. R. Leslie, “Lecture on the Works of the late William Etty,” pp. 349-352. 9 D. Farr, William Etty, (London, 1958), p. 103.

Exhibited:

London, Royal Academy, 1847, no. 123, p. 9.

London, Society of Artists, London, 1849, no. VII.

Condition:

The painting has just been restored a few months ago and is ready to hang as is.

Support: The painting is now on a stable canvas support. The stretcher is probably the original one

so it was not changed. It is strong and sturdy.

Paint layers: In natural light, the paint layers appear well preserved. The pigments are vibrant and

retain their original chromatic balance and richness. Most of the paint surface appears to be in

particularly good condition.

We can also notice some original obvious impasto and texture of the brushwork on the surface of

the artwork.

Under ultra-violet light, the following retouching from the new restoration can be seen (mostly on

the floor, the edges, and the background).

The painting has been recently re-varnished and is ready to hang as is. It is a fine example of the

outstanding technique of the artist William Etty.