Constance-Marie Charpentier

Une mère convalescente soignée par ses enfants

Provenance:

Artist’s collection.

Post-mortem inventory of François-Victor Charpentier dating to May 16, 1810: “It deux tableaux dont le père aveugle et l’autre la mère convalescente dans leurs bordures dorées (…).”

Collection of the heirs’ family, South of France; sale, Christie’s, Paris, 25 June 2019, lot 43, when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

G. Dacre-Wrigt, Constance Charpentier, peintre (1767-1849), online publication, pp. 69, 101, 103 and 104, and additif published online in September 2012.

Catalogue Entry

Fig. 1. Constance-Marie Charpentier, Melancholy, 1801, oil on canvas, Musée de Picardie, Amiens.

Constance-Marie Charpentier was one of the finest female painters in Paris at the turn of the nineteenth century. Although information about her training is scarce, she is believed to have been a pupil of Johann Georg Wille (1715–1808) and, since 1787, of Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), a painter who was notably supportive of female artists.1 Charpentier specialised in sentimental genre scenes, and portraits of women and children, which she regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon from 1795 to 1819, the year she was awarded the gold medal by the Royal Museum.2 One of the few allegorical paintings known by the artist, Melancholy (Musée de Picardie, Amiens, Fig. 1), is considered her masterpiece. Exhibited at the Salon in 1801, it received critical acclaim and became one of the most frequently mentioned works in contemporary historiography. After she ceased exhibiting her work, Charpentier continued her career by teaching painting to the new generations of painters, women included. A dictionary of the time mentions her “receiving, three times a week, young people who wish to follow her advice on drawing and painting”3 at her house in Rue du Pot de Fer Saint-Sulpice.

Fig. 2. Constance-Marie Charpentier, Une mère convalescente soignée par ses enfants, detail.

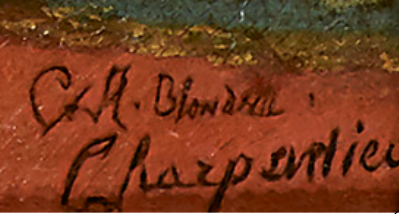

In the present work, a woman dressed in a white nightgown, wearing a shawl and a nightcap, has stood up from a bed visible in the background, on the right. As she struggles walking, she is aided by two of her children. The young woman holds a pillow, which she will place on the chair her younger brother is about to bring closer to their mother. The recovering woman’s youngest child, seen on the left with his/her back to the viewer, walks towards the group, while, on the right, another daughter placidly brings a cup of hot beverage. On the lower right of the painting is the artist’s signature, ‘C. M. Blondelu / Charpentier,’ which underlines the artist’s maiden name (Fig. 2). Charpentier was indeed born into the Blondelu family, changing her last name after marrying François-Victor Charpentier in 1793. Although she mostly signed her works with her married name, her alternative signature appears in other works, including the delicate Jeune fille à la perle (Fig. 3, Private collection).

Fig. 3. Constance-Marie Charpentier, Jeune fille à la perle, signed ‘Blondelu Charpentier fcit/1807’ (lower right), oil on canvas, 40 x 32.5 cm., Private collection.

Fig. 4. Constance-Marie Charpentier, Une jeune personne montrant à lire à sa soeur, oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm., Private Collection.

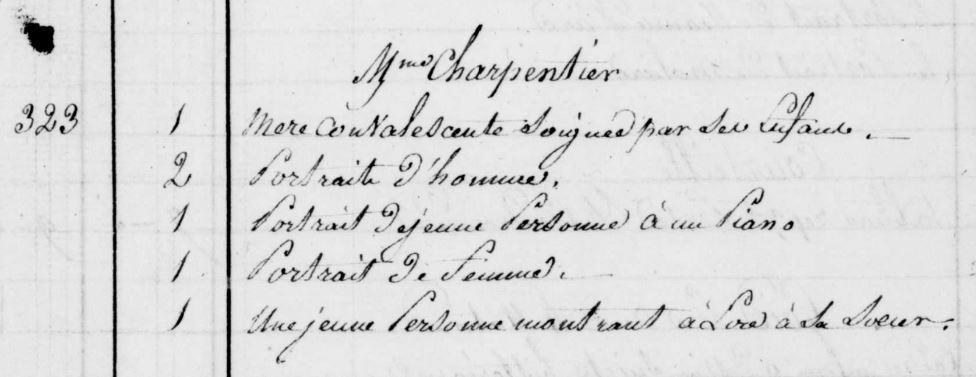

The provenance of the present work can be traced back to the time when it was painted. In the list of artists participating to the 1804 Salon, Charpentier is included under numerò d’ordre de reception 323.4 In that year, she presented Une mère convalescente soignée par ses enfants, Une jeune personne montrant à lire à sa soeur (Private collection, Fig. 4), as well as two Portraits d’homme, a Portrait de jeunne personne à un piano and a Portait de femme, which have not been identified (Fig 5). The painting is then mentioned in the post-mortem inventory of Charpentier’s husband, dating to May 16, 1810. The document alludes, on the one hand, to “two paintings, one of which depicting a blind father, the other a convalescent mother, both in gilded frames and estimated one hundred and forty-four francs,”5 on the other hand to “a copy of the convalescent mother by Mrs Charpentier priced fifty francs.”6 There were therefore two “convalescent mothers”: the present work, which has maintained the original gilded frame mentioned in the inventory and has remained with the artist’s descendants until it was sold at auction,7 and a now lost copy executed by Charpentier or someone else. The painting depicting the blind father has been identified as Un aveugle entouré de ses enfants est consolé de la perte de la vue par les jouissances des quatre autres sens (more commonly titled Les cinq sens, Fig. 6 ), a composition of great invention that was exhibited at the Salon in 1806.

Fig. 5. Registre de Musé Napoleon, Salon des Artistes Vivantes, Exposition de l’an 12, 1804, no. 323.

The present work can be included in the production of sentimental scenes of ordinary life that Charpentier started executing from 1796, when she presented Le compte-rendu sur l’anse du panier at the Salon. At the turn of the nineteenth century, it was customary for female artists to specialise in scenes of ordinary life and portraits, particularly of women and children. At the time, life drawing classes were still denied to women in both private and public institutions, as they were considered inappropriate for young ladies. Without access to drawing nudes from life, women could not get necessary training to successfully approach history and mythological painting, which ranked at the top of the traditional hierarchy of genres and was the most profitable. In order to make a living, female artists inevitably turned to lesser important genres: portraiture, genre painting – as in this case – landscape and still life.

Fig. 6. Constance-Marie Charpentier, Un aveugle entouré de ses enfants est consolé de la perte de la vue par les jouissances des quatre autres sens or Le cinq sens, oil on canvas, 1806, Private collection.

Une mère convalescente combines a Neoclassical spirit with an attention to contemporary actuality, as was distinctive of painting in the Napoleonic era.8 In their polished surfaces and frieze-like arrangement, the figures bear traces of the classicizing legacy of David. The stance of the girl on the far right, particularly, seems to have been modelled on figures of virgins or procession participants visible on ancient bass relieves, such as those that could be seen at the Louvre (Fig. 7 and 8). Although the young boy, the nicely-dressed young ladies, the elderly woman and the child might at first appear portrait-like, they are probably stock types from a repertoire to which Charpentier returned. For example, the profile view of the older daughter reappears several times in the artist’s production, including her own self-portrait (Fig. 9). Simultaneously, the painting is realistic in its setting, a distinctively early nineteenth-century French upper-class bedroom. Carpets with geometric motives, canopy beds, fireplaces surmounted by tall mirrors and clocks similar to those in the present canvas abounded in interiors of the time. All female figures do not wear sandals all’antica, as was customary in Neoclassical painting, but fashionable contemporary satin shoes.

Fig. 8. Plaque des Ergastines, 445-438 a.C., from Athens acropolis, Musée du Louvre, Paris © Musée du Louvre / Daniel Lebée et Caterine Deambrosis

Fig. 7. Left: Libation scene: Apollo kitharoidos and Nike, marble, c. 100 – c. 75 BC, Roman copy from Neo-Attic original; right: Constance-Marie Charpentier, Une mère convalescente, detail.

The eldest daughter’s gesture of bringing a pillow to make her mother comfortable when sitting down, along with the fire lit to warm the ill woman provide the painting with an aura of tenderness and palpable humanity. Considering the customary use of genre painting to convey moral messages, such a depiction of filial devotion might be read in the light of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s pioneering pedagogical writings, such as Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse and Emile. In the first book of the latter, which was published in 1762, Rousseau underlines that the child and the mother are bound with each other by reciprocal duties and affection. Through their educational role in families, mothers are expected to lead their children to become good men and good women, and are considered as essential agents of social stability. Une mère convalescente could therefore be read as a painting presenting an example of a successful mother – who has taken care of her children and is taken care of in return – to be imitated in order to contribute to the creation of a morally just society.9

Fig. 9. On the left : Constance-Marie Charpentier, Self Portrait, 1800; on the right: Charpentier, Une mère convalescente, detail.

1 “Constance-Marie Charpentier,” in Rebecca Morrill, Karen Wright and Louisa Elderton, ed., Great Women Artists, (London: Phaidon, 2019). 2 French Painting 1774–1830. The Age of Revolution, (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Art, 1975), p. 345. For a detailed biography of Constance-Marie Charpentier, see Gildas Dacre-Wrigt, Constance Charpentier, Peintre (1767-1849), online publication: http://www.constance-charpentier.fr/ 3 Charles Gabet, Dictionnaire des Artistes de L’école Française, au XIXème siècle, (Paris, 1831), pp. 132-133: “Mme Charpentier reçoit, trois fois par semaines [sic], les jeunes personnes qui désirent suivre ses conseils pour le dessin et la peinture.” 4 Musée Napoleon, Salon des Artistes Vivantes, Exposition de l’an 12, Registre, 1804. Last accessed October 16, 2020: https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/rechercheconsultation/consultation/ir/consultationIR.action?irId=FRAN_IR_054675&udId=c-3i1zkkz8n--1dnhkngxxdir2&details=true&gotoArchivesNums=false&auSeinIR=true 5 Inventory of François-Victor Charpentier: "(…) deux tableaux dont le père aveugle et l’autre la mère convalescente dans leurs bordures dorées prisés et estimés cent quarante-quatre francs." 6 Ibid., "(…) une copie de la mère convalescente de Mme Charpentier prisé cinquante francs." 7 Christie’s, Paris, 25 June 2019, lot 43. 8 French Painting 1774–1830, p. 173. 9 For Rousseau’s views on women and education of women, see Gilbert Py, Rousseau et les Educateurs, Etude sur la Fortune des Idees Pedagogiques de Jean-Jacques Rousseau en France et en Europe au XVIIIe siecle (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1997), pp. 338-405. For Rousseau's views on children, see Julia Simon, “Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Children,” in Susan M. Turner and Gareth B. Matthews, ed., The Philosopher's Child, Critical Essays in the Western Tradition (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 1998), pp. 105-120.

Exhibited:

Paris Salon, 1804 (titled Une mère convalescente soignée par ses enfants).