The city of Mantua celebrates one of the artists that most contributed to its splendour during the first decades of the Cinquecento, Giulio Pippi de’ Jannuzzi, better known as Giulio Romano (Rome 1492 or 1499 – Mantua 1546), with Giulio Romano. Arte e Desiderio, currently on view at Palazzo Te. The exhibition pays homage to the artist by investigating the fundamental role he played in shaping the erotic art of his time. Two of the exhibition curators, Dr Barbara Furlotti and Dr Guido Rebecchini lead us into the discovery of such an alluring project.

Increasing attention has recently been paid by scholarship in both publications and exhibitions to the interrelations between art, desire, eroticism and the nude, primarily in Art, Sexuality and Antiquity in Renaissance Italy by J. G Turner and in The Renaissance Nude shows at the Los Angeles Getty Centre and the London Royal Academy of Arts. If so, how did you relate to such studies when you researched similar themes in relation to Romano’s art?

James Turner’s book is a pioneering work, which builds on research previously done by Bette Talvacchia. It is a rich account of the importance of eroticism in sixteenth-century art, but largely focused on the relationship with the Antique. Turner, who contributed to our catalogue as well, is certainly right in considering erotic art a humanistic phenomenon. Indeed, in our exhibition, this aspect is a central theme, but we also wanted to highlight the courtly and political dimension of erotic art. In our exhibition, we have tried to show how erotic art was ironic, even comic, and belonged to a type of courtly culture which had its counterpart in the scandalous erotic comedies written by many authors for the lords of the day. The Renaissance Nude was a different exhibition altogether, as it did not deal with the erotic dimension of art, but with the emergence of the nude in religious art first and then in classical, normative works mostly concerned with idealised beauty or with anatomical studies. Both Turner’s book, and the Getty-Royal Academy show, to which we would add Jill Burke’s remarkable The Italian Renaissance Nude, try in different ways to reconsider the position of gender and sexuality in early modern art. In this respect, we believe that our exhibition contributes to the field with a distinct and complementary approach.

Considering that numerous extant Renaissance erotic cycles, such as those by Raphael in Rome and those by Romano in Palazzo Te, still remain in situ, which were the criteria that guided your selection of the works to be included in the show?

We have tried to represent the main erotic fresco cycles designed by Raphael in Rome through drawings and prints, mainly to indicate the ways in which they became known to a wide audience, beyond the selected group of those admitted to see them in the Vatican or in the Villa Farnesina. We have then shown how the infamous Modi designed by Giulio and engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, even though they were rapidly suppressed, were critical in the rapid diffusion of a real fashion for erotic, even pornographic imagery, where the titillating nature of the scenes was presented with irony and little concerns for decency. In the 1520s and 1530s, drawings, prints, maiolica, bronze statuettes furnished private rooms of art lovers, like Federico Gonzaga or his uncle Alfonso d’Este, and probably gave rise to amused discussions and to personal delight. We also wanted to discuss in this context the ubiquitous images of the Loves of the Gods, especially of Jupiter, which provided a literary excuse to represent erotic encounters. Often interpreted as moral episodes, imbued with virtuous meanings, these rather pertained to a visual culture of masculinity and were first and foremost about eroticism, conquest, even rape. We wanted to show a less palatable image of the High Renaissance, which scholars have often tried to normalise according to modern moral paradigms.

Numerous Roman artefacts are displayed across the exhibition, including a marble statue of Venus – possibly donated by Romano to the Duke of Mantua, Federico II Gonzaga – and a series of Spintriae, or brass tokens depicting erotic scenes. Similar objects led Renaissance artists to bring sensuality back into art by offering them an infinite variety of visual sources. How did Romano specifically relate to Classical antiquity when it came to erotic imagery?

Giulio Romano knew Roman art in depth. His inventions were informed by ancient statues, reliefs and probably even by erotic tokens like the Spintrie displayed in the exhibition, which were avidly collected in the Renaissance. However, Giulio seldom copied his models, they were sources of inspiration and allowed him a degree of freedom that few other artists of the sixteenth century explored. He was really “anticamente moderno and modernamente antico” as Pietro Aretino wrote.

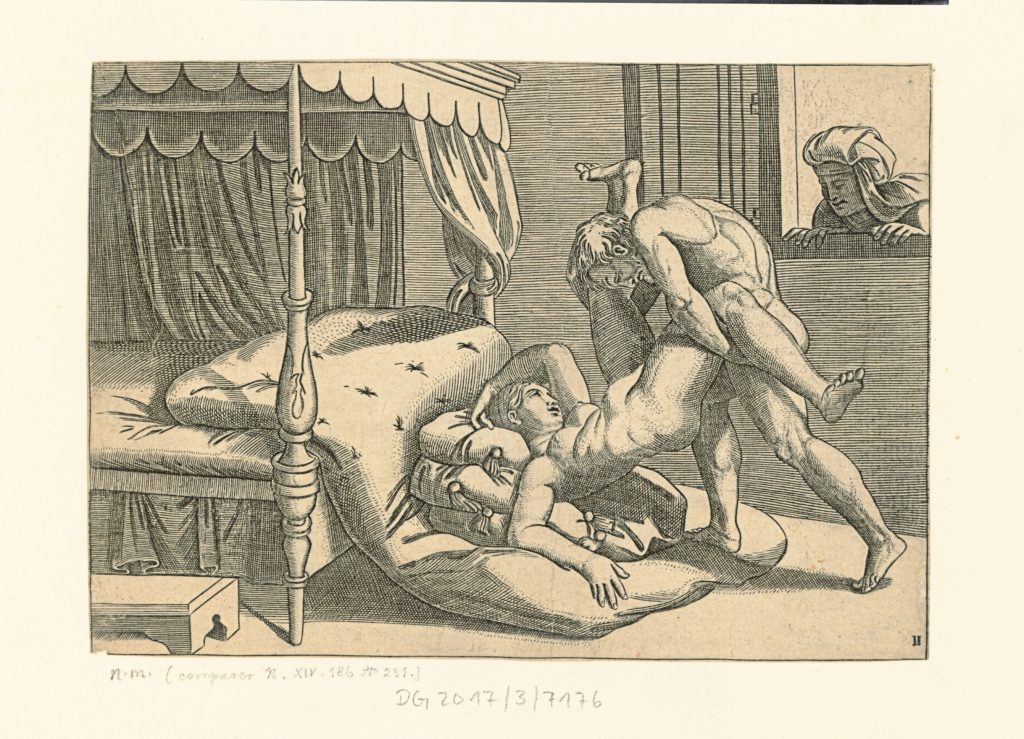

An entire section of the exhibition is dedicated to the Modi, a series of explicit images of sexual encounters drawn by Romano and accompanied by sonnets by Pietro Aretino, which were printed by Marcantonio Raimondi. Although these images were immediately censured and most of them destroyed due to their obscenity, they nevertheless became popular among artists, who borrowed their motifs even in non-erotic scenes, as exemplified in the exhibition by a maiolica plate by Francesco Xanto Avelli depicting the Tevere flood. Why did these apparently pornographic images have such a pervasive impact on early Cinquecento visual culture?

When the Modi were published, around 1524, it appears that there was an enormous appetite for these scandalous images. They were hugely influential, and yet so ephemeral. They appeared at a time in which Italian culture, though fraught with conflicts, seemed to revive the Golden Age of Leo X (1513-1521), after the austere and short-lived papacy of the Flemish Hadrian VI, when a new Medici pope, Clement VII, was elected in Rome. At the news of his election in 1523, there was a burst of joy and hope in his patronage, artists flocked to Rome to explore its antiquities and compete for commissions. Among the protagonist of this exuberant moment was Parmigianino, who came to Rome seeking fortune and copied one of the Modi in a rare and magnificent drawing on view in the exhibition. To add a further level of ambiguity, he transformed the heterosexual couple of Giulio’s drawing, into one which looks very much like a homosexual one. Cross-gender, homosexuality, and pederasty were fluid concepts at the time, as we can gather from the writings of Benvenuto Cellini or Pietro Aretino, and our display tries to visualise this elusive visual culture, which has come down to us through the filters of centuries of censorship.

The display of a copy of Raphael’s idealised Fornarina next to Romano’s more alluring Lady at the mirror on loan from the Puškin Museum seems to suggest two different approaches to depicting female nudity. Comparing the measured sensuality of Raphael’s nudes with the more explicit tone of those by his pupil, could we detect a different mindset behind their conception of erotic images and their agency?

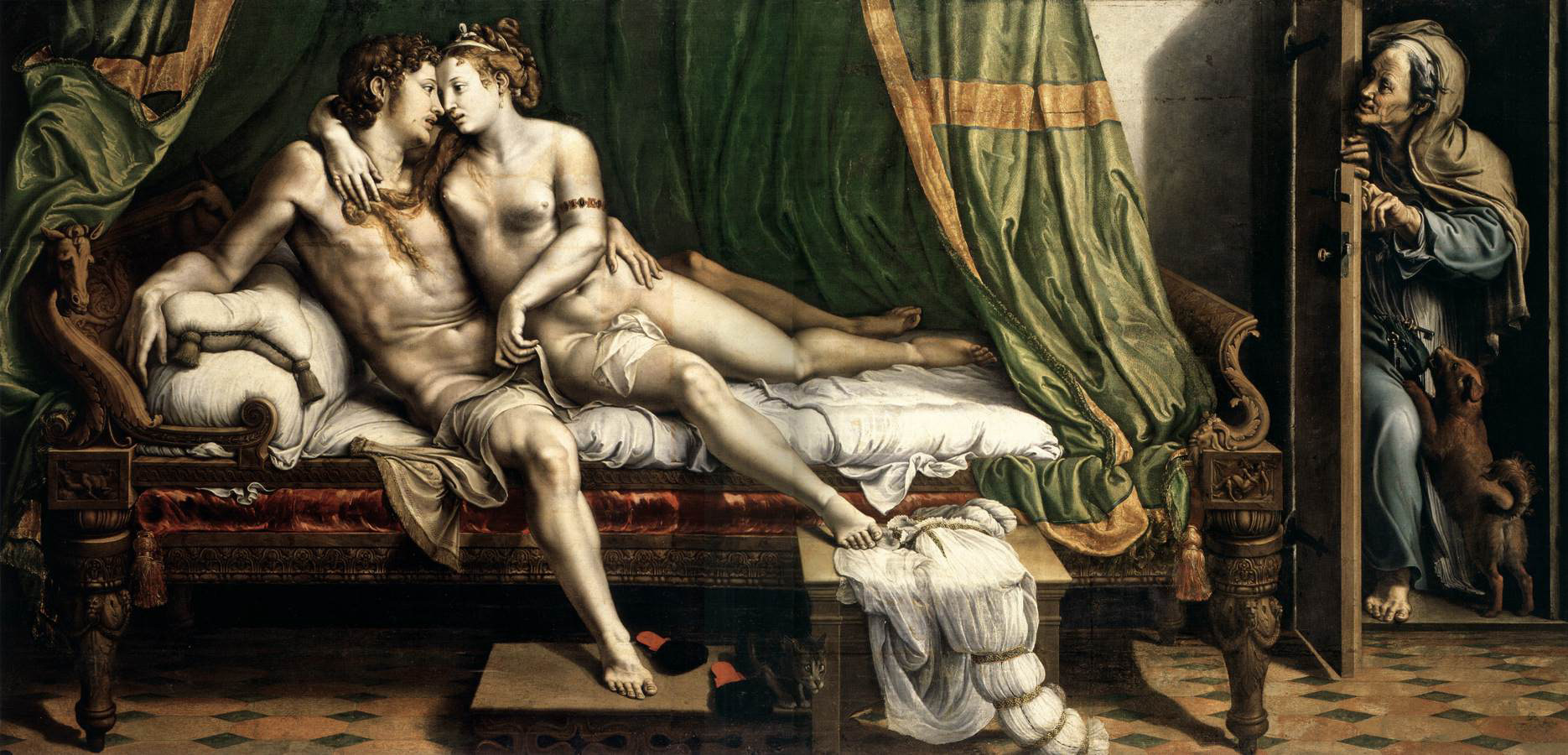

Indeed, we wanted the public to be able to appreciate the difference between Raphael’s idealised view of female beauty, and Giulio’s ‘domestic’ approach to the same. Clearly dependent on his master’s painting, Giulio translated into prose Raphael’s poetic image. The two paintings are so close to one another and yet so essentially different. The Puškin Courtesan is the perfect counterpart of the glorious painting of the Two Lovers from the Hermitage, the centrepiece of the exhibition.

In 1524, Giulio Romano left Rome and moved to Mantua, where he became one of the favourite painters of Federico II, a duke whose masculinity and prestige was often linked to his success with women. Considering the cultural role played by sensuality within Federico’s court, how did Romano respond to existing ideals when he painted erotic images such as those in Palazzo Te?

When he painted the Two Lovers around 1523-1524, Giulio Romano had Federico Gonzaga as its recipient in mind. He probably knew about his passion for erotic subjects. Federico had spent time in his youth in Rome and had seen Raphael’s Galatea in the Farnesina, and probably the Venus and Adonis by Sebastiano Luciani for Agostino Chigi, among many other works of erotic subject. When seeking new works of painting to add to his collection, Federico explicitly wrote that he wanted profane and leisurely works, not religious ones. Artists in Rome must have been thrilled upon hearing of this request. The Two Lovers were shipped to Mantua in 1526, when Giulio was settled in the city and had begun to know better his patron’s taste. In that year, Giulio was planning the execution of the frescoes of the Sala di Psiche in the Palazzo Te, which is a triumph of sensuality, of exposed flesh, and explicit amorous encounters. Such joyous imagery, must have powerfully resonated with Federico’s life. At the time, he was deeply engaged in an illicit relationship with Isabella Boschetti, for whom he felt and ardent and well-documented passion.

238.5 × 278.5 cm., Paris, Musée du Louvre,

–Cabinet des dessins

As previously mentioned and further exemplified at the end of the exhibition by a comparison between Romano’s Two Lovers and Perin del Vaga’s Jupiter and Danae, the success of Romano’s erotic compositions was enormous across northern and central Italy. Was there a specific legacy in Mantua, the city where the artist spent the last 22 years of his life?

No. After the death of Federico Gonzaga in 1540 and during the regency of Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga, Giulio Romano changed his repertoire radically. Ercole was a reforming prelate with no apparent interest for profane painting, and came to power in Mantua at a time of deep contrasts with the Protestants in Northern Europe. In those years, the Roman Curia was looking for a strategy to respond to the accusations of German theologians and was devising the criteria for its own reform. There was no more space for explicit sexual imagery, and sensuality was banned from the public eye. It was the dawn of the Counter –reformation, and Giulio’s subversive inventions were no more admissible.

Simultaneously to Giulio Romano. Arte e Desiderio, another outstanding exhibition at Mantua Palazzo Ducale, “Con una nuova e stravagante maniera.” Giulio Romano a Mantova, celebrates the artist’s inventiveness and extraordinary draughtsmanship through the display of numerous drawings, the majority of which was exceptionally lent by the Département des Arts Graphiques of the Musée du Louvre. In addition to revealing Romano’s versatility, the show offers the breath-taking opportunity to compare some of the drawings he executed for his fresco cycles in Palazzo Ducale, primarily for the Appartamento di Troia, with the frescoes themselves.

Giulio Romano. Arte e Desiderio

October 6, 2019 – January 6, 2020

Palazzo Te, Mantua

Con una nuova stravagante maniera. Giulio Romano a Mantova

October 6, 2019 – January 6, 2020

Palazzo Ducale, Mantua