The Frick Collection has just opened the first monographic exhibition on Florentine sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni (ca. 1140 – 1491): Bertoldo di Giovanni: The Renaissance of Sculpture in Medici Florence. By reuniting nearly his entire body of work – about twenty statuettes, reliefs, medals, along with his life-size statue of Saint Jerome and the terracotta frieze from the Medici Villa at Poggio a Caiano – the exhibition reveals the artist’s prominence within the artistic milieu of Laurentian Florence. Following in the footsteps of James David Draper’s 1992 monograph on Bertoldo di Giovanni, the New York show finally sheds light on an exceptionally multifaceted Renaissance sculptor. One of the curators of the show, Alexander J. Noelle, gives us a closer look into such an astonishing project.

Mentioned by Giorgio Vasari only in passing as a pupil of Donatello and a master of the Divine Michelangelo, Bertoldo di Giovanni was long underestimated. How does this exhibition change the narrative of fifteenth-century Florentine sculpture as we have known it so far?

Michelangelo studied with Bertoldo but, later in life, effectively wrote him out of his narrative, fashioning himself as a self-taught artist, divinely blessed with his abilities. Vasari’s characterization of Bertoldo also downplays his role, effectively utilizing Bertoldo as the connection through which Donatello’s creative genius was “inherited” by Michelangelo via Bertoldo, whose own artistic identity was, thus, suppressed; for Vasari, he was simply a vessel for the almost hereditary transfer of talent. However, documents produced during Bertoldo’s lifetime prove that he was heralded for his “grand ingenuity and artistry.” When Bertoldo died, for example, Lorenzo the Magnificent, his primary patron, was unsure if he would be able to find another sculptor of Bertoldo’s talents in all of Italy. Our exhibition, the first on Bertoldo, addresses this discrepancy by celebrating him in his own right, as he was during while he was alive. Instead of being defined by his connections to Lorenzo, Donatello, and Michelangelo, we explore how the understanding of this innovative sculptor is, instead, enhanced by his relationships with artists and patrons. We have revealed how Bertoldo occupied a unique position at the heart of the artistic and political landscape in Florence.

During your two-year work on this exhibition you devoted much time to researching the Frick Collection’s Shield Bearer, displayed here for the first time alongside his Liechtenstein pendant. What do these statuettes tell us about Bertoldo’s engagement with textual and visual sources, as well as his attitude towards narrative?

Bertoldo’s Shield Bearers seem to be mirror images. Both are nude — save for the vines encircling their bodies and the leaves crowning their heads — brandish shields, and wield clubs. They are, however, markedly distinct. The Frick Shield Bearer is younger and suppler, with small horns curling into the tousled locks above his forehead, as well as a swishing tail and set of panpipes that are revealed when the statuette is viewed from behind. The Liechtenstein figure is older and more muscular, with a full beard and none of his companion’s fantastical appendages. Designed to engage viewers as they examined the statuettes, the figures present multivalent identities, combining the iconography of wild men (legendary forest dwellers who were covered in hair and unnaturally strong), fauns (half-goat, half-human woodland creatures), and Hercules (the hero of Greek myth). Bertoldo reveled in the creation of objects that actively drew from (and departed from) a variety of textual and visual sources, thereby creating complex artworks that did not have straightforward narratives. His beguiling sculptures, instead, blend multiple iconographies and diverse narratives that create conversations instead of providing clear answers.

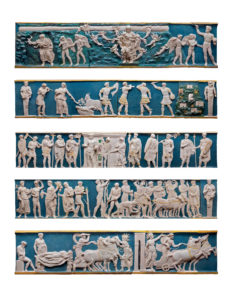

Bertoldo was a favourite and familiare of Lorenzo de’ Medici, who commissioned him with numerous works of art, including the frieze from his countryside villa at Poggio a Caiano – displayed in its entirety on this occasion for the first time outside of Florence – and the Pazzi Conspiracy medal. Considering your specific interest in Giuliano de Medici, whose patronage you investigated in your Phd dissertation, have you found any element suggesting he might have been one of Bertoldo’s patrons alike his brother?

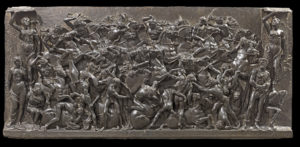

Because of Bertoldo’s proximity to the Medici, there are actually very few extant documents related to his production of artwork for them; perhaps their close relationship negated the need for contracts, payment records, etc. Therefore, it is almost impossible to tell, for most objects, who commissioned what from Bertoldo. It is clear, however, that Lorenzo and Giuliano operated in tandem. The tomb of their father and uncle, created by Verrrocchio, was commissioned by both brothers, as inscribed on its marble base, and, together, they sold Verrocchio’s David to the Florentine government. Bertoldo also depcits them in tandem in the Pazzi Conspiracy Medal, so, while there is no documentary evidence, it is highly likely that the Medici brothers both worked with Bertoldo in his creation of objects for the Medici, such as the incredible Battle relief.

After Bertoldo’s death, a notary described him as “a most worthy sculptor and an excellent maker of medals, who always made fine things with Lorenzo the Magnificent… who is now very troubled for there is no other artist in Tuscany or perhaps even Italy of such grand ingenuity and artistry in these things.” What do you think made Bertoldo’s work so special in comparison to other sculptors of his time?

The Pazzi Conspiracy medal, for example, was an incredibly innovative object. Unlike any other Renaissance example, it collapses the traditional obverse and reverse of a portrait medal, fusing the likenesses of the Medici brothers, allegorical figures, and historical narrative. Filled with scenes that retell the attempted coup, the assassination of Giuliano and salvation of Lorenzo unfold in the viewer’s hand as the medal is rotated, bringing the tragic events to life. The design, heralded as “immortal” at the time, was – and remains – truly unique. Bertoldo was exceedingly creative; his imaginative use of iconography (discussed above in relation to the Shield Bearers), inspiration derived from antique objects, and creative conceptions of composition, as evidenced by the Pazzi medal, combined to make him a singular artist, situated at the center of the Medici circle of artists, many of whom he worked with.

I would like to end our conversation asking you the same question you posed James David Draper in your interview at the beginning of the exhibition catalogue: what questions still remain?

We are very proud of the questions that the exhibition brings to light and poses to the viewer. While there are 100 documents that detail the life and artwork of Bertoldo, compiled for the first time in the catalogue, much remains unknown. It is clear that Bertoldo collaborated with many of the leading sculptors in Renaissance Florence, but it is not known who each of them were. Furthermore, while Bertoldo became the familare of Lorenzo, it is also not clear how they first met. However, the more interesting questions posed by the installation of the exhibition explore Bertoldo’s design across medium. How are his works in bronze, at a small scale, related to his 15-meter long terracotta frieze? If the two Shield Bearers were commissioned as a pair, how were they displayed together, and who were they made for? Bertoldo, we propose, was a modeler, collaborator, and teacher, working with the leading writers and artists of his day to realize his designs. How is that visible in his sculptures? Much remains to be discovered, but we have designed the exhibition, supported by the catalogue, to answer many of the longstanding questions surrounding Bertoldo while posing new queries that will lead to a better understanding not only of Bertoldo, but also the production of artwork in Medici Florence.