Abraham van Dijck

An old woman reading at a table

Provenance:

Collection of Robert D. Pflieger, Brussels (bought circa 1930); thence by descent to his nephew Jack Pflieger, Washington, DC; sale, Christie’s New York, 30 October 2018, lot 105, when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

W. Sumowski, Gemälde der Rembrandt-Schüler, Vol. V, Landau 1983, pp. 3093, 3181, no. 2050 (illustrated, as Abraham van Dijck, c. 1655/60).

Catalogue Entry

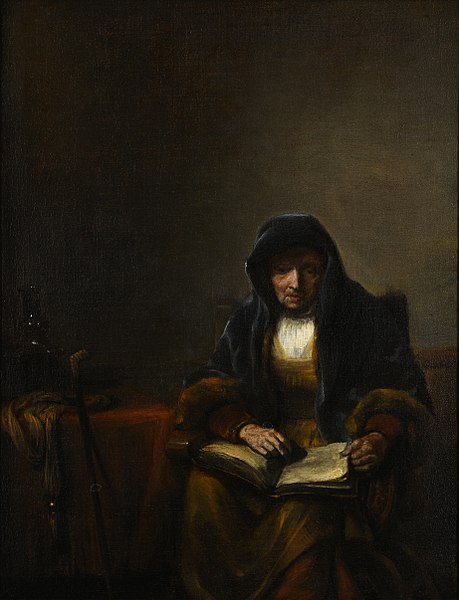

Abraham van Dijck (Dyck) was a Dutch painter and draughtsman of the Dutch Golden Age. His training and subsequent artistic development remain a matter of conjecture. Echoes of Rembrandt in his work often led scholars to hypothesise that he might have been one of his pupils, although there is no documentary evidence confirming this. Rembrandt’s impact on van Dijck might have been indirect, via the knowledge of the Leiden school of fine painters and, specifically, Nicolaes Maes, from whom van Dijck borrowed subjects, a dark colour palette and powerful brushstrokes. Similarly to Maes, van Dijck mainly painted domestic scenes and specialised in pictures of elderly women praying or reading at a table, among which the present work is a remarkable example.1

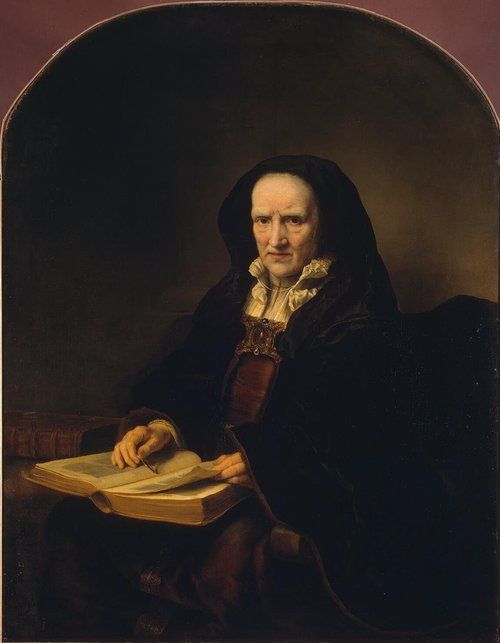

This painting has been known to scholars since 1953, when a photograph was deposited by the owner in the RKD in The Hague, where it was filed under the name of Abraham van Dijck.2 The work shows an old woman sitting by a table covered by a fur and a book. Although the volume’s letters cannot be discerned, its large dimensions suggest it is probably a Bible. The woman leans her head on her right hand, while she holds a pince-nez in her left hand resting on her lap. The figure wears a black hooded mantle preciously lined with fur over a dark dress embellished by a metal band and a white chemise in its upper section. A clear light falling from the upper left of the composition masterfully illuminates the woman’s face and, in revealing her fine wrinkles and dark circles, leads the viewer’s attention towards her pensive facial expression.

Fig. 2. Rembrandt van Rijn, An Old Woman Reading, oil on canvas, 80 x 66 cm., 1655, The Buccleuch Collection at Drumlanrig Castle.

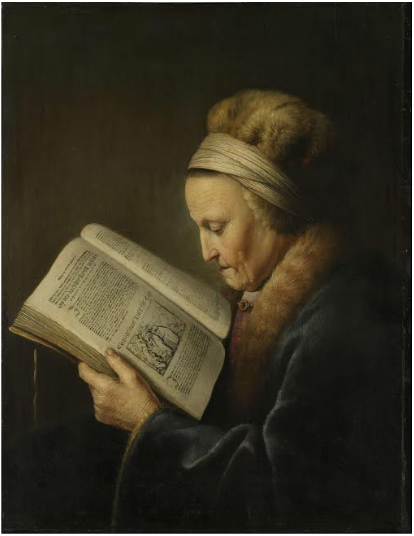

Fig. 1. Rembrandt van Rijn, Old Woman Reading, probably the Prophetess Hannah, oil on panel, 60 x 48 cm., Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam.

The present work exemplifies the upturn in the production of paintings of old women reading, praying or meditating, which occurred in Holland during the 1650s. Significant precedents can be found in Rembrandt’s tronies, or faces, of old women, many of which are believed to be based on the physiognomy of the artist’s mother.3 Works such as Rembrandt’s Old Woman reading in the Rijksmuseum (Fig. 1) and An Old Woman Reading at Drumlanrig Castle (Fig. 2) have often been interpreted as portraits historiés, or portraits of real women in the guise of prophetesses or sybils. Many are believed to depict prophetess Hannah, a senescent woman described in the Bible as serving God with fasting and prayers night and day.4 The presence in van Dijck’s work of a senile woman accompanied by a book, wearing a black hood almost identical to the one in Rembrandt’s painting (Fig. 2) might suggest a similar identification of the woman as a generic type of prophetess.

Fig. 3. Ferdinand Bol, Portrait of an Old Woman with a Book, oil on canvas, 129 x 100 cm., 1651, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Fig. 4. Gerard Dou, Old Woman Reading, oil on panel, 71.2 x 55.2 cm., c. 1631-1632, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

A visual analysis of the painting and a comparison with similar works from the period might suggest another possible interpretation. During the 1650s, Rembrandt’s pupils borrowed their master’s Biblical iconography to create more generic subjects reflecting ideas about old age and how the elderly should live.5 In works such as the present one, and, for example, Ferdinand Bol’s Portrait of an Old Woman with a Book (1651, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Fig. 3), the subjects’ warm, fur-trimmed garments are more reminiscent of aristocratic widows’ winter clothing rather than of oriental mantles usually characterising prophetesses and sybils. The association between cold and old age dates back to Aristotle, Juvenal and Maximilian, who ascribed men’s physical decline to the coldness of their blood. In his famous Iconologia, which had been known in the Netherlands since 1611,6 Cesare Ripa underlined the association between coldness and old age, defining the latter as the winter of a man’s life.7 Ripa described old age as an elderly woman holding a pair of spectacles in her hands, an attribute that also appears in van Dijck’s and Bol’s works in the shape of a pince-nez.

Fig. 6. Rembrandt van Rijn, St Jerome in a Dark Chamber, etching, engraving, and drypoint, second of three states, 15.3 x 17.6 cm., 1642, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

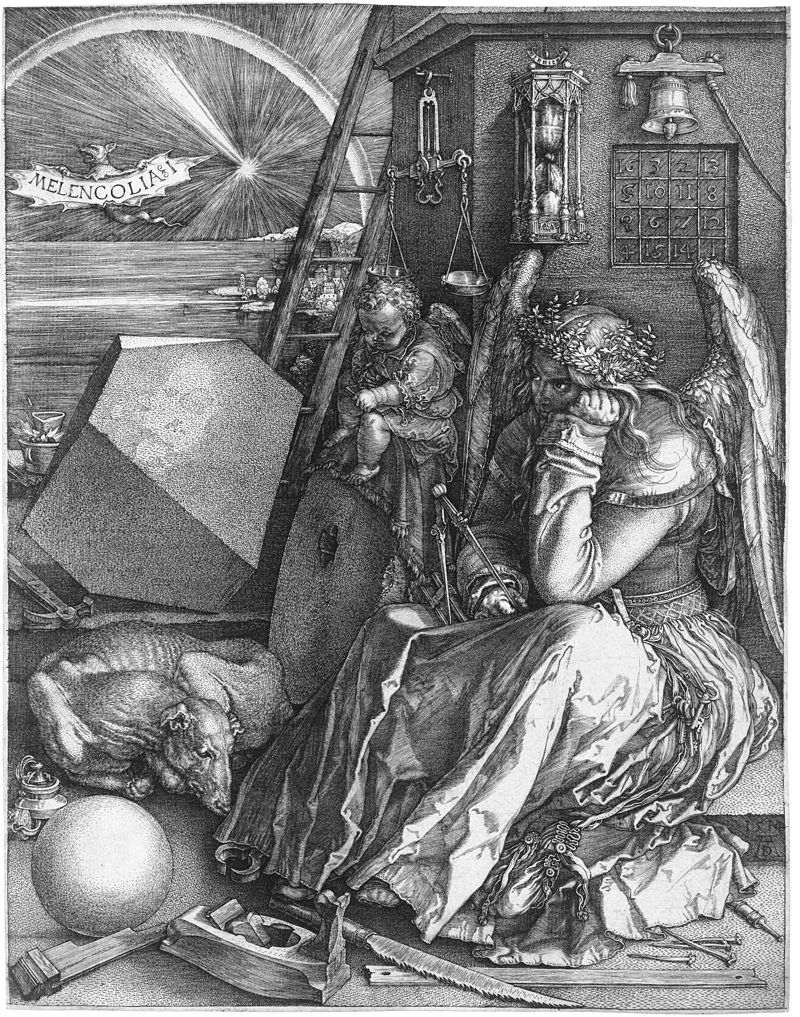

Fig. 5. Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, engraving, 24 x 18.5 cm., 1651, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

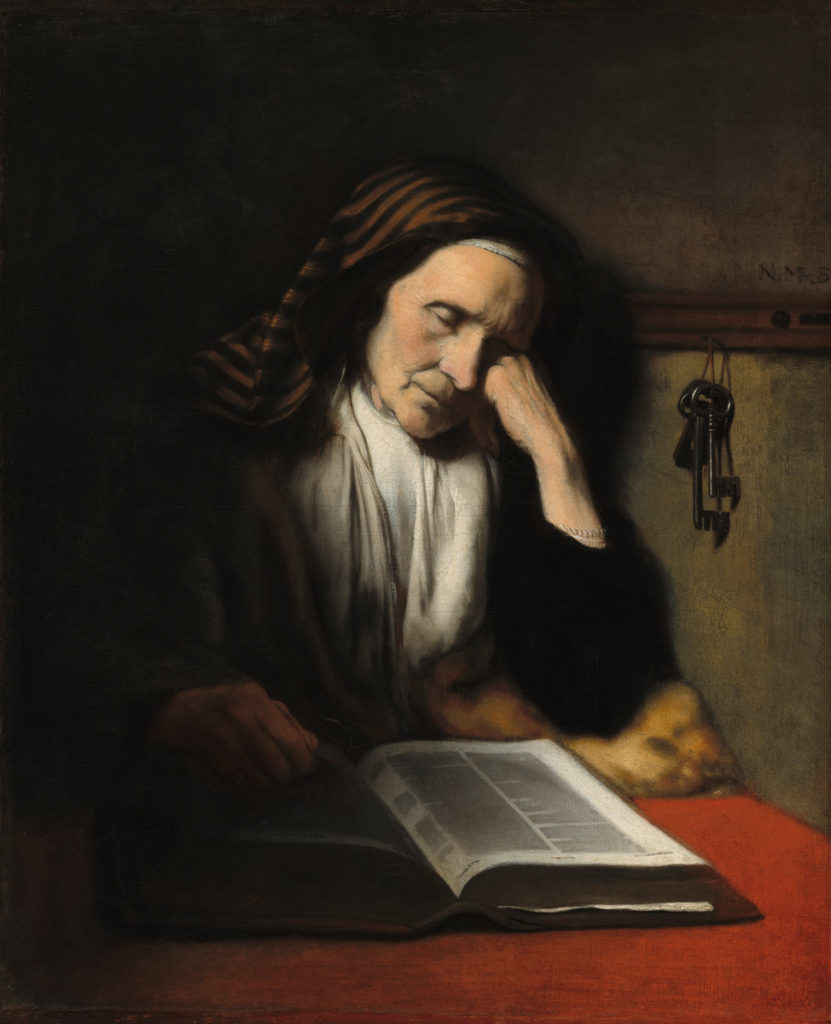

In An Old Woman reading at a table, the Bible occupies a peripheral area of the composition, being partially covered by a sumptuous fur. The woman is not engaged in reading the volume, as it happens in some of Gerard Dou’s portraits of old women (Fig. 4), nor she holds it in her hand as in Bol’s painting. She does not make eye contact with the viewer but seems rather immersed in her own thoughts, as if meditating on the sacred scriptures during a pause from reading. Her pensive mood is further reinforced by her pose, which recalls that of Albrecht Dürer’s famous engraving Melencolia I of 1514 (Fig. 5). This stance was very popular in seventeenth-century Northern painting, being associated to artistic inspiration, love and, at times, piety.8 The melancholic pose reflects piety and devotion in several representations of St Jerome, as exemplified by a Rembrandt’s etching (Fig. 6), which van Dijck probably knew.9 The artist might also have derived such a pose from Nicolaes Maes’ moralising paintings of elderly women (Fig. 7), which were one of his main sources of inspiration.10 In this light, the present work could be read in the context of contemporary ideas on old age and how women should live the final years of their lives, i.e. in piety, devotion and wisdom. The painting could essentially be interpreted as a Vanitas, where the old woman becomes an illustration of the transience of her own life. Only a pious conduct, and not her material possessions – exemplified here by the luxurious fur and decoration of her garments – will offer her hope for eternal life in the world to come.

Fig. 7. Nicolaes Maes, An Old Woman Dozing over a Book, oil on canvas, 82.2 x 67 cm., c. 1655, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fig. 8. Abraham van Dijck, Old Woman with a Bible (Old Prophetess), oil on canvas, 37.5 x 36.5 cm., c. 1655-1660, Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig.

The present work can be closely compared to van Dijck’s Old Woman with a Bible (Old Prophetess) in the Leipzig Museum der Bildenden Künste (Fig. 8). The two works present a similar composition: the subject is depicted in a melancholic pose alike, accompanied by a Bible, clearly recognisable from its locks, and by a pince-nez. The presence in the Leipzig painting of an extinguishing candle, the symbol par excellence of time passing, might reinforce a reading of these and similar paintings, such as van Dijck’s Old woman with book in the Dordrechts Museums (fig. 9) and his Old Woman with the Bible in The State Hermitage Museum (Fig. 10) as Vanitas. As previously mentioned, van Dijck derived these iconographies from Nicolaes Maes, who introduced them in Dordrecht in the mid-1650s. Their vast production suggests that the city, at the time a Calvinist stronghold, may have provided a ready market for paintings stressing piety and moral responsibility.11

Fig. 10. Abraham van Dijck, Old Woman with the Bible, oil on canvas, 133x 107 cm., 1655-1660, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Fig. 9. Abraham van Dijck, Old Woman with a Book, oil on canvas, 41 x 33 cm., 1655-1660, Dordrechts Museum.

With all this considered, one may hypothesise An old woman reading at a table to have been painted in around the mid-1650s. This might be confirmed by the strongly modelled face of the subject, which seems to reappear, slightly varied, in van Dijck’s aforementioned paintings dating to 1655-1660.

Stylistically, the present work could be compared to van Dijck’s Jacob’s Farewell to Benjamin (The Art Institute of Chicago, Fig. 11) dating to the 1650s. Indeed, the two works share a similar use of light, with strong contrasts of illuminated and dark areas. In both paintings, the artist set the figures convincingly in space not only through illumination, but also through a restricted, dark colour palette of blacks and muddy browns, applied with thick, vivid brushstrokes in the manner of Maes. The way of rendering the dress’ decorative band with impasto is then reminiscent of Rembrandt’s painting of the 1650s.

Fig. 11. Abraham van Dijck, Jacob’s Farewell to Benjamin, oil on canvas, 113 x 110.5 cm., 1650-1660, The Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

The present work will be included in the forthcoming monograph on the artist by Dr David de Witt, Abraham van Dijck c. 1635-1680. Life and work of a late Rembrandt pupil, which will be published in February 2020.

1 For biographical information on the artist, see J. Loughman, “Abraham van Dijck (1635?-1680), a Dordrecht painter in the Shadow of Rembrandt,” in His Milieu: Essays on the Netherlandish Art in Memory of John Michael Montias, (Amsterdam University Press, 2006), pp. 265-278. 2 I am grateful to Dr David de Witt for this information. 3 For a detailed study, see G. Korevaar and C. Vogelaar, Rembrandt’s Mother: Myth and Reality, (Zwolle: Waanders, 2005). 4 Ibid., p. 112. 5 Ibid., p. 129. 6 Ibid., p. 112. 7 C. Ripa and G. Z. Castellini, Iconologia di Cesare Ripa perugino caualier di SS. Mauritio et Lazaro diuisa in tre libri: ne i quali si esprimono varie imagini di virtù, vitij, affetti, passioni humane, arti, discipline, humori, elementi, corpi celesti, prouincie d'Italia, fiumi…, (Venice: Presso Cristoforo Tomasini(IS), Tomasini, Cristoforo, 1645), p. 184. 8 For a detailed study, see L. S. Dixon, The Dark Side of Genius: The Melancholic Persona in Art, ca. 1500-1700, (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013). 9 I own this comparison to Dr de Witt. 10 W. A. Liedtke, Dutch Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vol I-II, (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven (Conn.), 2007), pp. 743-744. 11 Ibid., p. 740.