Karel Philips Spierincks

The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and angels

Provenance:

Private collection (since the nineteenth century); sale, Bonhams, London, 7 July 2021, lot 69, when acquired by the present owner.

Catalogue Entry

Fig. 1. Karel Philips Spierincks, Venus Sleeping, with Satyrs and Cupids, c. 1630-1640, oil on canvas, 146.1 x 170.2 cm, The Royal Collection, London.

Fig. 2. Karel Philips Spierincks, Jupiter and Callisto, oil on canvas, 134.6 × 177.8 cm, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Flemish painter Karel Philips Spierincks was born in Brussels at the beginning of the seventeenth century, probably in 1600. Although biographical information on the artist is scarce, he is known to have been a pupil of Michel de Boerdous in 1612 and a master in the Brussels Guild of Saint Luke in 1622. By the end of the year, he moved to Rome, where he became known as Carlo Fiammingo (Charles the Flemish) or Carlo Filippo, and briefly trained with Paul Bril (1554-1626). In 1625, Spierincks is documented as living in the Strada Paolina with a fellow Flemish, the sculptor François Duquesnoy (1597-1643), who introduced him to Nicolas Poussin (1594-1660), with whom he had previously shared the same house. In the 1630s, Spierincks was one of the artists who participated in the Galleria Giustiniana, the enterprise publishing Vincenzo Giustiniani’s exceptional collection of classical sculpture. He died on May 22, 1639 and was buried near the high altar of Santa Maria della Pietà in Camposanto teutonico, leaving incomplete paintings for the sacristy of Santa Maria dell’Anima. Four pictures by Spierincks are known to have been owned by Flemish merchants in Rome: three Bacchanals are recorded in the inventory of Philips Baldescot in 1641 and a St Norbert (one of the Santa Maria dell’Anima canvases) was listed on March 2, 1643 in the house of Peter Vissche.

Fig. 4. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Worship of Venus, oil on canvas, 172 x 175 cm., 1518, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Fig. 3. Karel Philips Spierincks, Drunken Silenus, oil on canvas, 99.5 x 120 cm., Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Bruxelles.

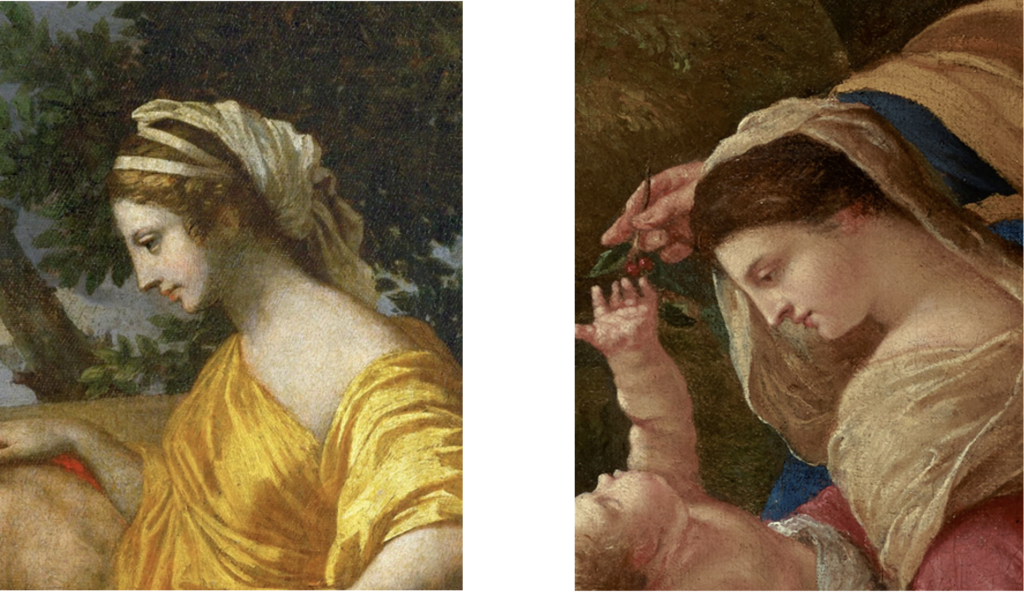

During his brief career, Spierincks specialised in mythological and pastoral scenes. The present painting is one of the few works of a religious nature known by the artist.1 It depicts the Holy family at rest in a landscape, arranged in a pyramidal structure. Mary, seen in profile, sits on the ground, holding Baby Jesus in her lap, while Saint Joseph offers him two cherries he picked from the tree behind them. The Infant Saint John the Baptist is depicted on the left, as he walks towards his cousin holding a lamb with both arms. The animal foreshadows Christ’s sacrifice, as does the cross made from reeds laying in the foreground, encircled by a scroll reading the first words the Baptist utters in St John’s Gospel (1:29): “Ecce Agnus dei” (Here is the Lamb of God). The scene is set in a verdant landscape, with trees and mountains in the distance. A group of three flying angel-like putti plays with cherry tree branches at the top left of the painting.

Scholar Anthony Blunt first put together Spierincks’ corpus of works in his article “Karel Philips Spierincks, the First Imitator of Poussin’s Bacchanals,” published in The Burlington Magazine in 1960. Blunt attributed a small number of paintings to the artist starting from a canvas of nymphs, satyrs and cupids in The Royal Collection, London (c. 1630-1640, Fig. 1), which was bought by Charles II in 1660.2 The group of works consisted of mythological and pastoral scenes in the style of Poussin. Spierincks was indeed one of the first artists to have looked at Poussin’s Bacchanals and mythological paintings of the early 1630s, and have produced personal variants on these themes, including his Jupiter and Callisto (The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Fig. 2) and the Drunken Silenus (Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Brussels, Fig. 3). Spierincks’ inventory, which was drawn up after his death at the request of Duquesnoy and Jean-Baptiste Cleissens, attests he was still working on Poussinesque subjects at the time of his death.3

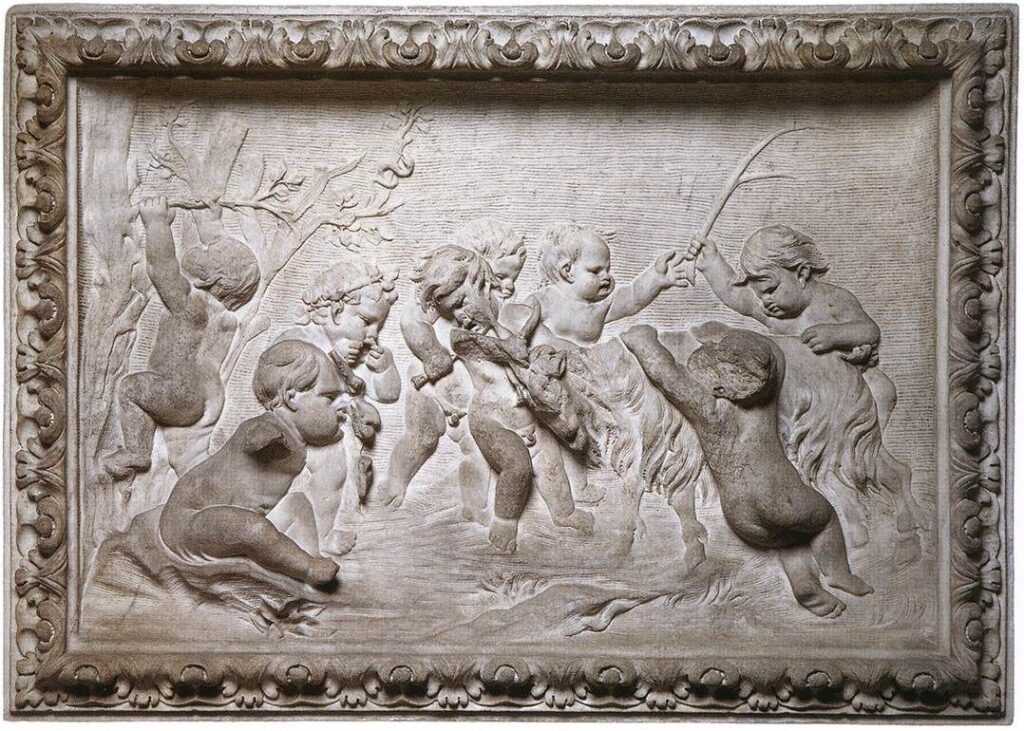

Fig. 5. François Duquesnoy, Bacchanal of putti with a goat, marble bass relief, 1630, Galleria Spada, Rome.

Fig. 6. Karel Philips Spierincks, Putti teasing a goat, oil on canvas, 140 x 220 cm, Private collection.

The influence of Poussin’s Bacchanals on the present canvas is suggested by the group of winged angels playing amidst the trees. These figures forecast Christ’s death by playing with branches full of cherries, which are traditional symbols of the passion.4 Their inclusion in the composition also exemplifies how the artist employed the type of subject matter he was most familiar with, which recurs in most of his paintings. As in the present work, in the London and Philadelphia canvases putti appear as flying in the air and amidst tree branches, their nudity occasionally covered by draperies. Spierincks derived the type from Poussin’s reading of Titian’s The Worship of Venus (Fig. 4, Museo del Prado, Madrid) – at the time in the Ludovisi Collection – where putti are shown in a variety of poses, including a few flying and picking fruits from a tree. Bellori narrates that Poussin reproduced the figures as terracotta models with the collaboration of Duquesnoy,5 a key figure in the development of the putti iconography in sculpture.6 Spierincks looked closely at Duquesnoy’s oeuvre, as attested, for example, by his painted version of the sculptor’s bas-relief Bacchanal of Putti with a Goat (Fig. 5 and 6). While working in Santa Maria dell’Anima, Spierincks probably came into contact with Duquesnoy’s Tomb of Ferdinand van den Eynde, whose left putto is closely comparable to the one flying in the present painting (Fig. 7 and 8).

Fig. 8. Karel Philips Spierincks, The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and angels (detail).

Fig. 7. François Duquesnoy, The Tomb of Ferdinand van den Eynde, 1633-1640, Church of Santa Maria dell’Anima, Rome (detail).

The profusion of putti in Poussin’s, Duquesnoy’s and Spierincks’ oeuvre speaks of an antiquarian interest that spread in Rome at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Artists were fond of Roman marbles, from where they took a repertoire of visual motives. In the present canvas, Spierincks’ interest in the Classical world is further exemplified by the figure of Mary, whose Greek profile and all’antica sandals are modelled after figures on ancient sarcophagi, in a similar way as Poussin did in his famous Et in arcadia ego in the Louvre (Fig. 9-12). The figures are enveloped in voluminous, statuesque draperies revealing Spierincks’ familiarity with the inspiration Duquesnoy drew from the canons of Classical sculpture.7

The slight disproportion between the figures’ bodies and their heads, particularly visible in Mary’s figure, is a distinctive feature of Spierincks’ style.8 The rendering of the landscape, with vegetation back-lit against a blue sky and the play of light on the foliage is also typical of the artist’s work, with a similar landscape appearing in the aforementioned Jupiter and Callisto. Spierincks’ refined sensibility in the rendering of landscape was doubtless influenced by the many landscape painters active in Rome in this period, including his master Paul Bril, as well as by Titian.

The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and angels came from a private collection in Australia.

Fig. 9 and 10. On the left: Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego, Musée du Louvre (detail); on the right: Karel Philips Spierincks, The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and angels (detail).

Fig. 11 and 12. On the left: Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia Ego, Musée du Louvre (detail); on the right: Karel Philips Spierincks, The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist and angels (detail).

1 The work was attributed to Spierincks by Dr Eric Schleier. 2 A. Blunt, “Poussin Studies X: Karel Philips Spierincks, the First Imitator of Poussin's Bacchanals,” in The Burlington Magazine, CII (1960), pp. 308-11. 3 S. Danesi Squarzina, “A ‘Hagar and the Angel’ by Carel Philips Spierinck in Potsdam,” in The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 141 (Jun., 1999), pp. 349–351. 4 In Italian painting, cherries were used in religious paintings to symbolize Christ’s blood. See, for example, Titian’s Madonna of the Cherries (1518, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien) and Barocci’s painting of the same title (1573, Vatican Museums, Vatican City). 5 G. P. Bellori, Le Vite de’ Pittori, Scultori e Architetti Moderni, (Rome 1672, ed. Turin 1976), note 20, p. 289. 6 See, for example, his bass-relief Triumph of sacred over prophane love (Galleria Doria Pamphili, Rome). 7 M. Becccari, “A ‘Saint Sebastian’ by Karel Philips Spierincks,” in The Burlington Magazine, July 2020, p. 596. 8 Ibid.

Condition:

The painting is in very good condition, with no major damages visible. It has recently been cleaned.