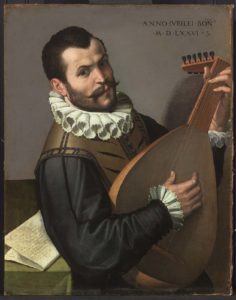

Santi di Tito

Portrait of a gentleman, three-quarter-length, in a black embroidered silk doublet and cloak, with a ruff, holding gloves and a letter in his left hand, a lute on the table

Provenance:

Marquis Dufour Berte, Palazzo Guadagni, Florence (according to an inscription on the reverse).

Private collection, Florence; sale, Christie’s, London, 9 July 2015, lot 10, when acquired by the present owner.

Catalogue Entry

Born in Sansepolcro in 1536, Santi di Tito was one of the leading painters, draughtsmen and architects in Florence during the second half of the Cinquecento, playing a pivotal role in the transition from Mannerism to the Baroque. Mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his Vite and by Raffaello Borghini in his treatise Il Riposo, the artist initially trained with Bastiano da Montecarlo and soon made his way to the workshops of Agnolo Bronzino (1503 – 1572) and Baccio Bandinelli (1488 – 1560), where he was introduced to the art of painting and drawing respectively.1 Living in Rome from about 1560 to 1564, Santi di Tito collaborated with Federico Zuccari (1539 – 1609) and Federico Barocci (1528/1535 – 1612) in the execution of the frescoes in the Villa Pia. After returning to Florence, he became a member of the Accademia del Disegno and received prestigious private and public commissions. He completed works for some of the most important churches in the city, such as Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce, and was involved in the execution of the apparati for Michelangelo’s memorial celebration and for the wedding of Francesco I de’ Medici. During the 1570s, under the guidance of Vasari, Santi di Tito contributed to the decoration of Francesco’s studiolo in the Palazzo Vecchio.2

Although Santi di Tito was primarily a painter of frescoes and altarpieces, he also worked as a portraitist. The artist depicted important personalities of his time, such as Galileo Galilei3 and several members of the Medici family.4 Although only few portraits by the artist survive today, his engagement with portraiture is attested by literary sources. In Il Riposo, Borghini recalls numerous portraits by the hand of di Tito and presents him as one of the most accomplished portraitists in Florence.5 In his Delle Notizie de’ Professori del Disegno da Cimabue in Qua, art historian and politician Filippo Baldinucci affirms that the artist painted portraits “with great ease,” executing his sitters’ heads and hands himself, while often leaving the rest to his assistants.6 Furthermore, the posthumous inventory of Santi di Tito’s house and workshop lists numerous portraits by his hand – mostly of unknown sitters – thus attesting that he was a prolific portraitist.7

The present work is one of the most refined extant portraits by Santi di Tito. The more than a half-length figure of a young man dressed in black stands in a simple setting looking out at the viewer. He wears a black silk cloak and doublet, embroidered with a fine rhombus decoration. Black are also his fashionable trunk hose, elegantly lined with black velvet. Standing out against the man’s dark clothing are his shirt’s white collar and cuffs. The sitter holds a letter and a pair of gloves in his left hand; in his right hand he holds what appears to be a bag. On the lower left hand corner of the panel, the neck of a lute appears.

Fig. 1. Francesco Salviati, Portrait of a Young Man with lute, oil on canvas, 1529-1530, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris.

Fig. 2. Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of a Young Man with lute, oil on board, 1532-1540, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Although the identity of the sitter is still unknown today, his elegant attire, the precious ring on his finger and the presence of the musical instrument suggest that he was a well-educated individual of high social class. The inclusion of the lute is particularly emblematic of the sitter’s status. The present work is indeed one of the several Mannerist portraits of young men, where musical instruments appear. At times, they are a prominent part of the composition, as in Francesco Salviati (1510-1563)’s Portrait of a young man with lute (1529-1530, Fig. 1), today at the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris. Other times they are almost entirely concealed, such as in the present work and in Bronzino’s famous Portrait of a young man with lute (1532-1534) in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence (Fig. 2). As pointed out by musicologist Victor Coelho, these portraits speak of the “values of a new, young Florentine culture,” whose identity was defined by the study of music coupled with the literary arts. From the 1530s onwards, the madrigal – a type of musical composition based on vernacular poetry – had become the main cultural expression of aristocratic youth in Florence, being performed within the domestic space for private pleasure.8 With all this considered, the presence of the lute in The Portrait of a gentleman thus denotes the sitter not as a musician, yet as a learned, courtly amateur.

The present painting is unanimously believed to date to the 1590s, as was suggested by Italian art historian Mina Gregori in 1965.9 Gregori substantiated her hypothesis by finding visual similarities with The Wedding at Cana (Scandicci, Giogoli, Villa I Collazzi ) and the Vision of Saint Thomas Aquinas, both dating to 1593 and sharing an intense use of chiaroscuro. In the present painting, Santi di Tito’s attention to light effects is attested by the clear light coming from the upper left, which illuminates the sitter, and leaves the right part of his face and body in the shade. Alike in the present work, in other portraits by the artist, such as the posthumous Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Fig. 3) and The Portrait of a Senator (Private collection, Fig. 4), the sitters’ physical presence is suggested by the casting of their shadows onto the wall behind them.

Fig. 4. Santi di Tito, Portrait of a senator, oil on panel, Private Collection

Fig. 3. Santi di Tito, Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli, oil on panel, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Such an attention to light effects is distinctive of Santi di Tito’s naturalistic style. By the 1590s, the artist had moved away from the idealism and artificial quality of Mannerist painting. Di Tito’s progressive stylistic change likely originated from his adhesion to the principles of the Counter Reformation, which, since the 1560s, had fostered compositional clarity and simplicity of form in painting.10 It may also have derived from the artist’s knowledge of Emilian portraiture, particularly of that of Bartolomeo Passarotti (1529-1592).11 Portraits of young men executed by the artist (ex. Fig. 5) share with the present work a similar interest in depicting the sitter’s real appearance and attention to light effects. The sitter in The Portrait of a gentleman strikes the viewer with his naturalistic features, his cheeks reddening in front of the viewer. Despite his youth, a few wrinkles across his forehead suggest the man has started aging. Di Tito’s sense of naturalism is then revealed in the accurate rendering of the man’s hands, characterised by redden knuckles. The artist’s bravura is then suggested by the exceptional rendering of the tactile qualities of fabrics and use of different shades of black to design the sitter’s outfit.

Fig. 5. Bartolomeo Passarotti, Portrait of a man playing a lute, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The present work was originally in the collection of Palazzo Guadagni, one of the most important palaces in Renaissance Florence. Located in Piazza Santo Spirito, the palazzo was commissioned by silk merchant Riniero di Bernardo in the first years of the Cinquecento, about thirty years before Santi di Tito was born.

1 Raffaello Borghini, Il Riposo, (Florence: 1584), 619. 2 For biographical information on Santi di Tito, see Gunter Arnolds, Santi di Tito. Pittore di Sansepolcro, (R. Accademia Petrarca Editrice: Florence, 1934), 3- 69. 3 Paolo Molaro, “On the Lost Portrait of Galileo by the Tuscan Painter Santi di Tito”, in The Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, vol. XIX, no. 3, 255-263. 4 For an overview of Santi di Tito’s portraits of the Medici family, see Karla Langedijk, The Portraits of the Medici, 15th – 18th Centuries, (Florence: Studio per edizioni scelte, 1981), under ‘Santi di Tito.’ 5 Borgini, Il Riposo, 619-620. 6 Filippo Baldinucci, Delle Notizie de’ Professori del Disegno. Tomo VII. Buonta Lenti, Giovanni Bologna, Sofonisba Angosciola, A. Lottini. Firenze, Stecchi and Pagani. 7 See Julian Brooks, “Santi di Tito’s studio: the contents of his house and workshop in 1603”, in The Burlington Magazine, CXLIV, 1190, May 2002, 279-288. 8 Victor Cohelo, “Bronzino’s Lute Player: Music and Youth Culture in Renaissance Florence,” in Renaissance Studies in Honor of Joseph Connors, ed. Machtelt Israëls and Louis A. Waldman, (Florence: Villa I Tatti, 2013), 650-659. 9 Mina Gregori, Settanta Pitture e Sculture del ‘600 e ‘700 Fiorentino, (Florence: Vallecchi, 1965), 41. 10 Alessandra Giannotti and Claudio Pizzorusso, Puro, Semplice, Naturale nell’Arte a Firenze tra Cinque e Seicento, (Florence: Giunti, 2014), 66. 11 Gregori, Settanta Pitture e Sculture, 41.

Exhibited:

Florence, Palazzo Strozzi, 70 pitture e sculture del ‘600 e ‘700 Fiorentino, October 1965, no. 2.