Jacopino del Conte

Portrait of a gentleman

Provenance:

Palazzo Capponi, Florence.

Vicomte Jules de Peyronnet (1804-1872).

Thence by descent to his granddaughter, Lady Mary Isabel Peyronnet Browne (1881-1947), Mount Browne, Guildford, Surrey; her deceased sale, Christie’s, 12 March 1948, lot 114, as ‘Bronzino’, “Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli,” (120 gns. to Agnew’s, London).

Thos. Agnew and Sons, London (as ‘Bronzino’).

Private European collection; sale, Christie’s, London, 8 December 2015, lot 17, when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

S. Lecchini Giovannoni, “Alcune proposte per l’attività ritrattistica di Alessandro Allori,” in Antichità viva, VII, 1, 1968, pp. 53 and 54, fig. 11, (as ‘Alessandro Allori’).

F. Zeri, “Rivedendo Jacopino del Conte,” in Antologia di belle arti, VI, 1978, p. 120, fig. 14.

F. Zeri, “Rivedendo Jacopino del Conte,” in Giorno per giorno nella pittura. Scritti sull’arte italiana del Cinquecento, Turin, 1994, p. 81, fig. 137.

M. Corso, “Jacopino del Conte nel contesto artistico romano tra gli anni trenta e gli anni cinquanta del Cinquecento,” Phd diss.; Università degli Studi Roma Tre, 2014, p. 177 (illustrated p. 445, fig. 150).

Catalogue Entry

Florentine painter Jacopino del Conte was one of the greatest portraitists in sixteenth-century Rome. In the 1568 edition of his Vite, Giorgio Vasari lists del Conte among the pupils of Mannerist painter Andrea del Sarto.1 The art historian affirms that the artist portrayed the most important personalities of the Roman aristocracy and all the Popes of his time, as biographer Giovanni Baglione also wrote about a century later.2 Indeed, after moving to Rome in the late 1530s and painting a fresco cycle in the oratory of San Giovanni Decollato, Jacopino del Conte dedicated himself to portraiture almost exclusively. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ignatius Loyola and Pope Paul III were among the most famous personalities portrayed by the artist.3

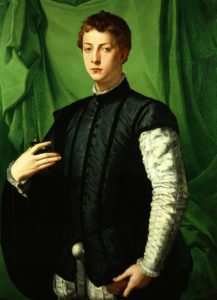

The present work is a fine example of del Conte’s activity as a portraitist. The picture shows the more than a half-length figure of a young man in three-quarter pose dressed in a fashionable black velvet doublet enriched with fur and a white lace collar. The sitter also wears a matching black cap. As he looks out of the canvas at the viewer, the man holds a pair of leather gloves in his right hand and rests his left hand on a book placed vertically on a table covered by a reddish cloth. The man stands before a green curtain, which covers the majority of the picture’s background. On the left are simple architectural elements and a window, from where light enters the scene illuminating the sitter and casting his shadow on the table.

Fig. 1. Agnolo Bronzino, Lodovico Capponi, 1550–55, oil on panel, 116.5 x 85.7 cm., The Frick Collection, New York.

Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of a Young Man, 1530s, oil on wood, 95.6 x 74.9 cm., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Portrait of a gentleman was originally ascribed to Agnolo Bronzino,4 whose work del Conte may have encountered in Florence. The frequent presence of curtains in Bronzino’s portraits (Fig. 1) and the similar disposition of the sitter’s hand on a book in his Portrait of a Young man (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fig. 2) may have suggested such an attribution. In 1968, Simona Lecchini Giovannoni ascribed the present work to Alessandro Allori, because of the lateral illumination of the painting – a distinctive feature of Allori’s portraiture – and the careful rendering of hands.5 On January 28 of the following year, Italian art historian Federico Zeri – who wrote his graduate thesis on del Conte – informally attributed the Portrait of a gentleman to the artist by annotating his name on the reverse of a picture of the work.6 Zeri formally advanced the attribution to del Conte only ten years later when, in a scholarly article, he included the Portrait of a gentleman within the artist’s corpus of works.7 The attribution is today commonly accepted by scholarship.8

Fig. 3. Jacopino del Conte, Portrait of Niccolò Gaddi, oil on canvas, 110.5 cm × 94 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien.

Comparison with other portraits by Jacopino del Conte reinforces Zeri’s attribution from a visual point of view. In del Conte’s Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Gaddi (Fig. 3), today at the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum, the background composition is very similar to that of the present work. On the left, are the same architectural structures, with lateral light falling through an identical window. In both paintings, it illuminates the sitters, revealing the precious materials of their garments. As in the Portrait of a gentleman, in the Vienna painting a curtain covers the rest of the background and Niccolò Gaddi holds a pair of gloves, one of his fingers slightly more bent than the others. This detail also appears in another work by del Conte, the Portrait of Bindo Altoviti (Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Montréal, Fig. 4). The present work can also be compared to the Portrait of Paul III with Ottavio Farnese (Fig. 5), where the aspect and bearing of Ottavio are closely reminiscent of those of the young man in the Portrait of a gentleman.

Fig. 4. Jacopino del Conte, Portrait of Bindo Altoviti, oil on wood, 128 x 102 cm., Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, Montréal.

Fig. 5. Jacopino del Conte, Portrait of Paul III with Ottavio Farnese, Barsanti Collection, Rome.

Comparison with the Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Gaddi, dating to about 1545, suggests that the present work was probably executed during the mid- or late 1540s.9 From a stylistic point of view, the scooped-out folds of the curtain, along with the impassible face of the Portrait of a gentleman’s sitter, his heavy-lidded eyes and bulbous nose are all distinctive features of del Conte’s portraits of that period,10 recurring, for example, in the aforementioned Portrait of Bindo Altoviti dating to about 1550.

Although the sitter of the present work was often believed to be Niccolò Machiavelli,11 there is neither visual nor documentary evidence confirming such an identification. The identity of its sitter thus remains unknown today. Considering that, as written by both Vasari and Baglione, del Conte mainly worked for the Roman aristocracy of the time, the man in the Portrait of a gentleman probably belonged to that social elite. His elegant doublet – which is reminiscent of that of Ottavio Farnese (Fig. 5) – suggests that he was a nobleman or an aristocrat. This might be confirmed by the presence of the book, possibly a poetry book, which would have underlined the sitter’s erudition. The figure’s self-controlled image, the simple background and the lack of excessive ornamental details fitted in with the austere and puritanical visual culture characterizing the early years of the Counter Reformation. Using Federico Zeri’s words on del Conte’s portraiture, the young man’s emotionless expression resulted from the “substitution of the real face with a mask, which was operated by the Tridentine Catholicism.”12

Originally located at Palazzo Capponi in Florence, the Portrait of a gentleman later entered the collection of Baron Jules de Peyronnet. The work was then inherited by his granddaughter, Lady Mary Isabel Payronnet Browne (1881-1947). Born in London in 1881 and defined as “a remarkable woman born to a remarkable family,” she never received a formal scientific education but, nevertheless, made major contributions to the fields of botany and palaeobotany. In addition to her scientific interests, Lady Mary Isabel Payronnet Browne was also a refined art collector and a very humanitarian person, earning an OBE for her assistance in tracing wounded or missing soldiers during WWI.13

1 Giorgio Vasari, Le vite d’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, 1568, ed. Paola Barocchi, vol. VI (Florence: Sansoni, 1987),p.222. 2 Giovanni Baglione, Le vite de' pittori, scultori, architetti, e architetti, dal pontificato di Gregorio XIII. del 1572. In fino a' tempi di Papa Urbano Ottavo nel 1642 scritte da Gio. Baglione romano e dedicate all’Eminentissimo e Reverendissimo Principe Girolamo Cardinal Colonna, (Roma: Stamperia di d’Andrea Fei, 1642), p. 75. 3 Federico Zeri and Elisabeth E. Gardner, Italian Paintings. A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Florentine School, (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971), p. 204. 4 Catalogue of pictures by old masters, the properties of Lady Isabel Mary Peyronnet Browne, O.B.E., deceased, late of Mount Browne, Guildford (sold by order of the executrix), Lady Mary Isabel Peyronnet Browne, Walter Dunkels, Esq. of Walhurst Manor, Cowfold, M.W.T. Leatham, Esq., Lady Vyvyan, Charles Wilmers, Esq., deceased, late of 11, Connaught Square, W.2, and others, (London: Christie, Manson & Woods, 1948), lot 114. 5 Simona Lecchini Giovannoni, “Alcune proposte per l’attività ritrattistica di Alessandro Allori,” in Antichità viva, VII, 1, 1968, p. 53. 6 I own this information to the Fondazione Federico Zeri, Bologna. 7 Federico Zeri, “Rivedendo Jacopino del Conte,” in Antologia di belle arti, VI, 1978, p. 120, fig. 14. 8 The attribution is supported by Michela Corso in “Jacopino del Conte nel contesto artistico romano tra gli anni trenta e gli anni cinquanta del Cinquecento,” Phd diss.; Università degli Studi Roma Tre, 2014, p. 177, and by expert Antonio Vannugli. 9 Zeri, “Rivedendo Jacopino del Conte,” 81. 10 Iris H. Cheney, “Notes on Jacopino Del Conte,” in The Art Bulletin, vol. 52, No. 1 (Mar., 1970), pp. 37 and 39. 11 The present work is conventionally titled Portrait of a gentleman (Niccolò Machiavelli) in almost all the literature and provenance’s sources. 12 Zeri, “Rivedendo Jacopino del Conte,” 81. 13 See H.E. Fraser & C. J. Cleal, “The Contribution of British Women toCarboniferous Palaeobotany during the first half of the 20th Century,” in Cynthia V. Burek & Bettie Higgs, The Role of Women in the History ofGeology, Geological Society of London, (London: The Geological Society, 2007), pp. 60-63.

Condition:

The present work was originally painted on a wooden panel and was later transferred onto canvas to consolidate the paint layer. This might be because the panel had become unstable or distorted.

There are old cracks running through the picture, which can be seen in raking light. The painting is covered with a glossy varnish. Although there are numerous vertical lines of restoration addressing old cracks and losses, much of the paint layer is in quite good condition and stable. Under ultraviolet light, it can be seen that the sitter’s face has received well applied retouches. There are a couple of thin cracks, which have been restored in the forehead and around the nose. The right edge has received a small addition. There is a small scratch in the varnish in the neck of the figure.