Bolognese School, second half of the sixteenth century

Portrait of a lady, in a red, gold and green dress, her right hand resting on a basket

Provenance:

Private collection, by 1949.

Lucien Baszanger, Geneva, by 1950.

Sale (The Property of the late Mrs. Hazel Westbury), Christie’s London, 9 December 2015, lot 162, (as ‘Bolognese school, 16th century’), when acquired by the present owner.

Bibliography:

L. Réau, Les Maîtres Anciens de la Collection Baszanger, Geneva 1950, no. 110, p. 132 (as ‘Paolo Veronese’, illustrated pl. XXXII).

L. Réau, Les Maîtres Anciens de la Collection Baszanger, Geneva 1957, no. 109, p. 59 (as ‘Paolo Veronese’).

Catalogue Entry

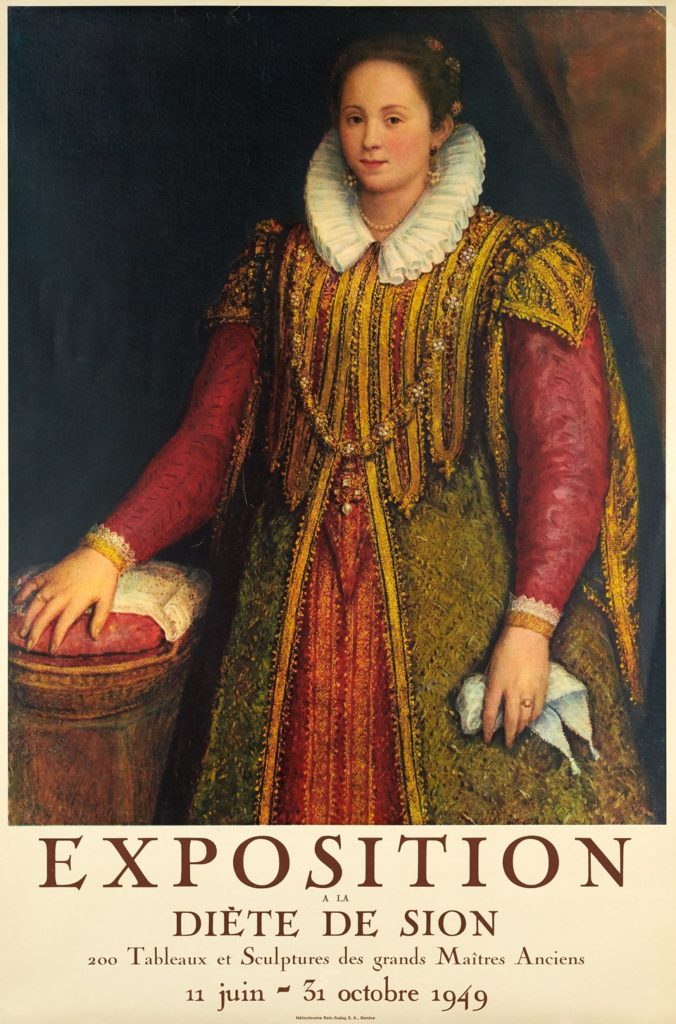

Fig. 2. Poster of the exhibition Exposition de la Maison de la Diête de Sion. 200 Tableaux et Sculptures des Grands Maitres Anciens, Maison de la Diète, Sion, 1949

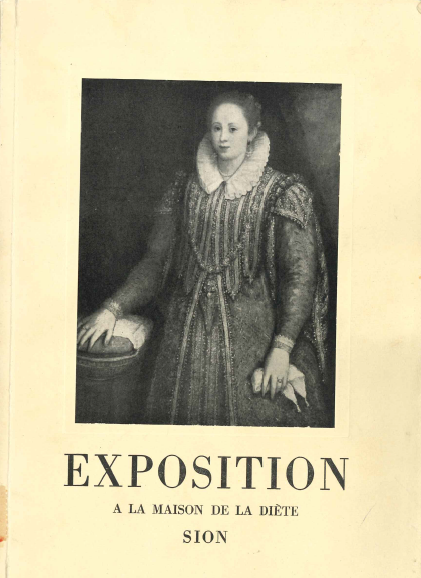

Fig. 1. Cover of the exhibition catalogue Exposition de la Maison de la Diète de Sion. 200 Tableaux et Sculptures des Grands Maitres Anciens, 1949.

The young lady portrayed in the present work communicates a combined sense of material opulence and demure elegance. Depicted in almost full length, the sitter stands against a dark back wall, framed by a curtain on the right. The woman wears a green over-garment with open sleeves, preciously embroidered in gold thread, over a similarly embroidered red silk robe with lace cuffs. The woman’s neck is surrounded by a white starched ruff, worn loose to reveal a string of pearls. The woman’s outfit is embellished with magnificent jewellery. Although partially discoloured, a lavish necklace lowers down on the woman’s bosom. It is made of a succession of plaques of chased and enamelled gold, set alternatively with large pearls and precious stones, and of a pendant with diamonds and a large pearl drop. Both of her hands are adorned by rings also set with diamonds, while her ears are embellished with a sophisticated pair of pearl bunch earrings. The woman’s blond hair is carefully styled with curls arranged along the front hairline and a knotted braid enriched with flower-shaped brooks. The sitter holds a handkerchief with whitework and needle lace in her left hand, while she rests her other hand on a wicker basket with a pillow covered by another handkerchief.

Fig. 4. Alessandro Allori, Portrait of Grand Duchess Bianca Cappello and her Son, oil on canvas, 128.4 x 100.5 cm., c. 1580–1614, Dallas Museum of Art, The Karl and Esther Hoblitzelle Collection, gift of the Hoblitzelle Foundation.

Fig. 3. Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait of Eleonora de’ Medici (?), oil on canvas, 106 x 67 cm., c. 1580, Museo Lazaro Galdiano, Barcelona.

The earliest reference to the present work dates to 1949, when it was included in an exhibition displaying two-hundred Old Master paintings and sculptures – including works by Bernardo Bellotto, Moretto da Brescia, and Jacopo Bassano – organised at the Maison de la Diète, an eighteenth-century mansion in Sion, France, which was transformed into an art gallery by an antiquarian in the twentieth century. On that occasion, the painting was ascribed to Paolo Caliari, better known as Veronese,1 and was selected as the image of both the catalogue cover (Fig, 1) and the exhibition poster (Fig. 2). By 1950, the work is documented in the refined collection of Swiss jeweller Lucien Baszanger, which included works by important European masters, with a vast representation of Flemish and Dutch artists, including Rembrandt, Van der Helst, and Cornelis van Haarlem. In the 1950 and 1957 editions of Les Maîtres Anciens de la Collection Baszanger, the painting is catalogued again as by Veronese,2 an attribution that was accepted also on the occasion of two exhibitions displaying a selection of works from Baszanger’s collection: an exhibition held at the Museum Het Prinsenhof in Delft in 1953 – documented by an original label on the painting’s reverse3 – and a 1954-1955 exhibition at the Geneva Musée d’Art et d’Histoire.4 A change in attribution occurred in 1999, when Sotheby’s New York catalogued the painting as attributed to Sofonisba Anguissola.5 In 2015, when the portrait was sold at Christie’s London, it was ascribed to the sixteenth-century Bolognese school.

The Portrait of a Lady thus has a complex and fascinating history of attribution. The original association with Veronese might have been suggested by visual similarities with Venetian sixteenth-century female portraiture, which often adopted the almost full-length format and showed lavishly dressed women with blond hair, a distinctive feature of Venetian noblewomen during the sixteenth century.6 If, alike the attribution to Veronese, the ascription of the Portrait to Sofonisba Anguissola was also subsequently discarded, it correctly reconducted the work to the Italian northern area. Indeed, scholarship agrees today with Christie’s attribution to the sixteenth-century Bolognese school. Although there seems to be no particular affinity with the most important portraitists of sixteenth-century Bologna, i.e. Bartolomeo Passarotti, Prospero Fontana, and Lavinia Fontana, the author of the present work was certainly aware of the latest trends in contemporary portraiture, as confirmed by the use of a curtain to frame the portrayed and by her pose, both being compositional formats that reappear in other portraits from the period, such as Anguissola’s alleged Portrait of Eleonora de Medici (Fig. 3).

Fig. 5. Giovan Battista Moroni, Portrait of Pace Rivola Spini, oil on canvas, 197 x 98 cm., c. 1573-1575, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, and detail.

If the identity of the Portrait’s author thus remains mysterious, the sitter’s outfit suggests the work was likely executed during the last decades of the Cinquecento. The woman’s dress follows the Spanish fashion, which spread across Italy from the 1540s onwards, after Eleonor of Toledo became Duchess of Florence. The embroidery of the woman’s red robe, running downwards in parallel lines, the pointed end of her corset and the slashed sleeves are recurring features in Spanish fashion, which came to characterise Italian fashion from the 1570s onwards (Fig. 3 and Fig 4). In particular, the chic detail of the Spanish ruches collar became fashionable in Italy after about 1570, appearing in a similar version in the Portrait of Pace Rivola Spini, painted by Giovan Battista Moroni in c. 1573-1575 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7. Lavinia Fontana, Portrait of Ginevra Aldrovandi Hercolani, oil on canvas, ca. 1595, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Fig. 6. Lavinia Fontana, Portrait of a Noblewoman, oil on canvas, 115 x 89.5 cm, c. 1580, National Museum of Women in the Arts, New York.

Although the woman in the Portrait remains unidentified, it is clear from her sumptuous costume that she belonged to the Bolognese patriciate. Visual elements suggest the work to have been probably executed on the occasion or shortly after the sitter’s marriage, as was customary at the time. The woman’s face is that of a young lady, possibly in her early twenties, the age of maximum fertility for women when they were expected to marry.7 The colour red, characterising the woman’s robe, was a traditional colour for wedding in Bologna,8 as Lavinia Fontana’s Portrait of a Noblewoman attests (Fig. 6).9 The sitter’s hair, worn up and not loose, testified to the woman’s marital status, as also did her rings.10 Her highly expensive clothing and jewellery signalled the magnificence of her family and would have acted as a sort of painted dowry inventory of a selection of her valuable possessions. As attested by extant portraits of Italian and Bolognese noblewomen (Fig. 7), fazzoletti, or handkerchiefs, were very popular accessories amongst the Italian élite during the sixteenth century and, being associated with decorous behaviour, were often included in a woman’s dowry.11 As well-known symbols of purity, pearls were common attributes for brides, as also were diamonds. Rubies – visible in the woman’s necklace – were the gems most frequently given to brides, as they were believed to promote bodily strength and prosperity.12 The marriage portrait hypothesis is further reinforced if one considers that Bolognese sumptuary laws, which aimed at regulating ostentatious display of wealth by private individuals, allowed women of the nobility to wear lavish outfits only on the occasion of their marriage and shortly after.13

Fig. 8. Portrait of a Lady, detail.

Despite the profusion of precious materials, the overall effect conveyed by the portrait is that of decorous elegance. The woman’s dress covers her body entirely and does not reveal any hint of her silhouette. The cross-shaped decorations of the over-garment’s fringes (Fig. 8) – the cross being a recurring element in Early Modern Spanish fashion – underlined the woman’s Christian piety. The basket on the left of the painting probably alluded to maternity. Indeed, very similar objects appear in sixteenth-century Bolognese painting as references to this theme, as substantiated, for example, by two Annunciations by Annibale and Ludovico Carracci (Fig. 9 and 10), where the basket alludes to Mary’s conception of Christ. The presence of the basket in the Portrait thus aimed at underlining the woman’s future role in maintaining the family’s lineage or, would she have been already married, it might have hinted at an ongoing pregnancy. It this case, the painting could have been specifically commissioned to celebrate the forthcoming birth of a child.

Fig. 9. Annibale Carracci, The Annunciation, oil on canvas, 134.6 x 98.4 cm., Private collection, and detail.

Fig. 10. Ludovico Carracci, The Annunciation, oil on canvas, 182.5 x 221 cm., 1584, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna, and detail.

We are grateful to Dr Babette Bohn for confirming the attribution to the Bolognese School, second half of the sixteenth century.

1 Exposition de la Maison de la Diête de Sion. 200 Tableaux et Sculptures des Grands Maitres Anciens, (Sion: Imprimeri-lithographie Fiorina & Pellet, 1949), no. 12, p. 23. 2 L. Réau, Les Maîtres Anciens de la Collection Baszanger, (Geneva: Mont Blanc, 1950), no. 110 (illustrated pl. XXXII), and L. Réau, Les Maîtres Anciens de la Collection Baszanger, (Geneva: ATAR arts graphiques, 1957), no. 109, p. 59. 3 The label on the reverse reads: 'STEDELIJK MUSEUM 'HET PRINSENHOF', DELFT' (handwritten), 'Tentoonstelling: Vijftig Werken Coll: Baszanger / Kunstenaar: Paolo Galiari Gen Veronese / Titel: Portret van een Dame / Eigenaar: L. Bazanger / Adres: Geneve.' 4 Cent Tableaux de la Collection Baszanger, (Geneva: Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, 1955), p. 37, no. 88. 5 Sale, Sotheby’s New York, 14 October 1999, lot 5 [as ‘Sofonisba Anguissola (attrib.)’]. 6 See Konrad Bloch, “Blondes in Venetian Renaissance Paintings,” in Konrad Bloch, Blondes in Venetian Renaissance Paintings, the Nine-Banded Armadillo, and Other Essays in Biochemistry, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 1-13. 7 Mary Rogers and Paola Tinagli, Women in Italy, 1350-1650. Ideals and Realities. A sourcebook, (Manchester: Manchester Univeristy Press, 2005), p. 167. 8 Babette Bohn, “Female Self-Portraiture in Early Modern Bologna,” in Renaissance Studies, vol. XVIII, no. 2, p. 254 9 See the website of the National Museum of Women in the Arts: https://nmwa.org/works/portrait-noblewoman. Last accessed on May 12, 2020. 10 David Alan Brown, Virtue and Beauty. Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2001), p. 94. 11 For a detailed study, see Bella Mirabella, “Embellishing Herself with a Cloth: The Contradictory Life of The Handkerchief,” in Ornamentalism: the Art of Renaissance Accessories, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011). 12 Allan Brown, Virtue and Beauty, p. 67. 13 For a detailed study on sumptuary laws in Bologna, see Maria Giuseppina Muzzarelli, La Legislazione Suntuaria. Secoli XIII-XVI. Emilia Romagna, (Roma: Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali. Direzione generale per gli archivi, 2002).

Exhibited:

Sion, Maison de la Diète, Exposition de la Maison de la Diète de Sion. 200 Tableaux et Sculptures des Grands Maitres Anciens, 1949, no. 12, p. 23 [as ‘Calliari Paolo (dit Paul Véronèse)’, illustrated on the cover page].

Delft, Museum Het Prinsenhof, Vijftig werken uit de collectie Baszanger te Genève, 1953, no. 44, pp. 17-18 (as ‘Paolo Caliari. Gen. Veronese’).

Geneva, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Cent Tableaux de la Collection Baszanger, 1954-1955, no. 88, p. 37, (as ‘Paolo Veronese’).