Abraham van Dijck (Amsterdam 1635/6-1672) was a skilful painter and draughtsman of the Dutch Golden Age. His works can be found in internationally leading museums, including The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. Yet, the first monographic volume on the artist, Abraham van Dijck c. 1635-1680. Life and work of a late Rembrandt pupil, has only recently been completed and is expected to be released in mid-May. Author Dr David de Witt gives us an insight into his ambitious publication.

Throughout your career, you have written extensively on several seventeenth-century Dutch painters, including Rembrandt, Jan van Noordt, Govert Flinck, and Jacob Backer. What drew you to devote a monographic study to the art of Abraham van Dijck?

It was the sense of intrigue that arose as I was researching one of the three paintings by the artist in The Bader Collection, as Bader Curator of European Art at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada. It gradually became clear that the artist had employed one of the most sophisticated recent developments in the work of his teacher, Rembrandt, which we call “isolation”. In his depiction of the biblical theme, namely the prophet Elijah, he left out significant figures and details, and made the scene about the inner experience involving a moral dilemma and profound human emotion. Even though Van Dijck was not nearly as well known as his friend and fellow pupil Nicolaes Maes, he engaged more deeply with the great achievement of Rembrandt’s late period, i.e. the evocation of inner experience and emotion. I wanted to know how and why, and share this with the world.

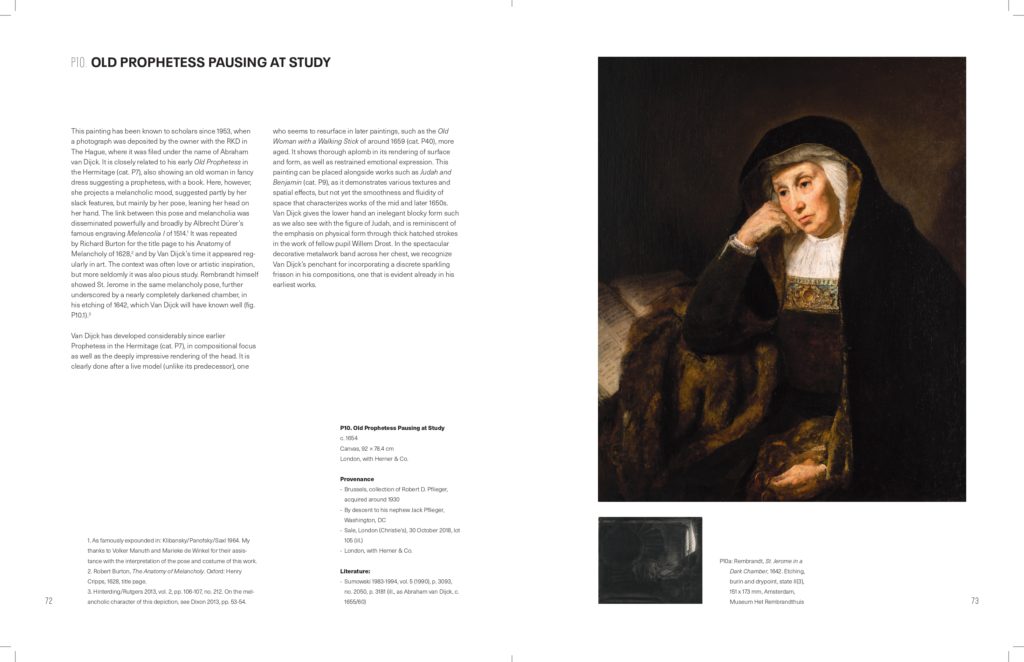

An old woman reading at a table, 92 x 78.4 cm., oil on canvas, with Herner & Co

Van Dijck’s artistic training and, particularly, his apprenticeship with Rembrandt have long been a matter of conjecture. The title of your volume, however, provides a clear statement on this matter. What kind of evidence has allowed you to affirm that van Dijck did study with Rembrandt?

This was indeed not an obvious point at the start of my research. However, through my analysis of several works and their place in the artist’s oeuvre, it became clear that they reflected a direct absorption of Rembrandt’s way of working right around 1652 to 1654. The most important work for this was a painting of an Old Prophetess in the Hermitage, showing Van Dijck working with direct and open brushstrokes, and letting go of the fine and smooth manner he had applied before coming to Rembrandt. I should add that we fortunately have two signed paintings that reflect the style he applied beforehand: we have this kind of evidence for very few pupils.

How did you structure the volume?

The book’s structure reflects the artist’s stylistic development. There are separate chapters dedicated to Van Dijck’s biography and draughtsmanship. Three other chapters discuss his works in terms of their chronology and logical order, divided into three well-defined periods to demonstrate the artist’s development and confirm the place of each work in the master’s oeuvre. This needed to be done first, as it reflects the current state of research. However, many other aspects are discussed along the way. Because we know nearly nothing about the market for van Dijck’s work or early owners, there was no occasion to devote attention to this aspect of his career.

Our painting An old woman reading at a table has been included in your publication with a dedicated catalogue entry. How do we place this work within van Dijck’s oeuvre?

It is part of the exciting early phase of response to Rembrandt’s work. It relates to the Old Prophetess in the Hermitage, as it shows experimentation with open brushwork and rough textures. This places it round 1654.

Can your publication be considered Abraham van Dijck’s first catalogue raisonné?

Can your publication be considered Abraham van Dijck’s first catalogue raisonné?

Definitely. The first major step towards the creation of a catalogue raisonné was taken by Werner Sumowski in the volumes of his Gemälde der Rembrandtschüler (Paintings of Rembrandt’s Pupils) and in his Drawings of the Rembrandt School. Yet, as Sumowski always emphasized, these publications were meant to feed further research on these artists.

This year has been very important for the rediscovery of lesser studied Dutch Golden Age painters. In addition to your book, the exhibition recently devoted to Nicolaes Maes at the London National Gallery also comes to my mind. Do you think that such projects will encourage further studies on other sixteenth-century Dutch painters sill living in the shadow of Rembrandt?

There is always the risk that scholars will think that such a research is not necessary anymore, that all has been done already, or others (especially the younger generation) will see it as impossible, given the high demand of stylistic analysis and technical research. This kind of work still needs to be done, and cannot be done without financial and institutional support. In my specific case, Bader Philanthropies was very important in making this exciting project possible.