Exhibition review | Antonello da Messina at the Royal Palace of Milan

May 11, 2019 | by Elena Caslini

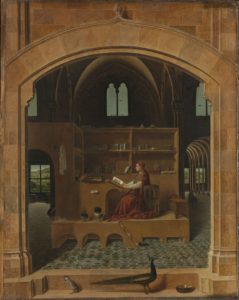

It is rather strange to go to the London National Gallery and notice that one of the most important paintings in its collection is not there. Antonello da Messina’s Saint Jerome in his Study (Fig. 1) is not hanging in its usual place. It has crossed the Channel to arrive in Milan for an exhibition entirely dedicated to its author.

Antonello Da Messina, Saint Jerome in his Study, c. 1475, oil on panel, 45.7 x 36.2 cm. The National Gallery, London © The National Gallery, London

The National Gallery would not have deprived its visitors of one of its most precious gems if not for a good cause. The exhibition Antonello da Messina, which opened in February at Milan Palazzo Reale coming from Palazzo Abatellis (Palermo), is one of the most complete exhibitions ever dedicated to one of the greatest yet mysterious painters of the fifteenth century. Nineteen of the thirty-five works attributed to Antonello da Messina (1430-1479) are exhibited in the show. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has lent Antonello’s Portrait of a Young Man (Fig. 2), while the Washington National Gallery of Art has granted the presence of the artist’s Madonna with Child (Fig. 3) to the exhibition. Several Sicilian museums may feel rather lonely at the moment, having lent some of their masterpieces, primarily Palazzo Abatellis, whose iconic Annunciata (Fig. 4) has made its way up north.

Fig. 2. Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Young Gentleman, oil on panel, 32.1 x 27.1 cm., Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection.

© Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection.

Fig. 3. Antonello da Messina, Madonna and Child, oil and tempera on panel transferred from panel, 58.1 x 43.2 cm., National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Collection. © National Gallery of Art, Washington.

The Milan exhibition provides insights into Antonello’s training and the painter’s relationship with his native town, Messina, one of the most multicultural crossroads of the Mediterranean during the fifteenth century. In the city, the artist was exposed to Flemish, Northern, Catalan, and Provençal pictorial languages, which he assimilated and combined in his paintings. Messina was also where the artist likely found the contacts that led him to spend one year working in Venice (1474-1475). There, quoting Vasari, he taught Domenico Veneziano “the secret and the art of oil paint” and he portrayed “numerous Venetian noblemen.”1 Some of these portraits are gathered in the exhibition, along with other half-length depictions of Sicilian noblemen, including the enigmatic Portrait of a Man (Fig. 5) today in Cefalù. The exhibition also addresses Da Messina’s technique and the reconstruction of some of his works, such as the San Cassiano altarpiece, which were destroyed during the 1693 and 1908 devastating earthquakes.

Fig. 5. Antonello da Messina, Portrait of a Man, oil on panel, 30.5 x 26.3 cm., c. 1470, Museo della Fondazione Culturale Mandralisca, Cefalù. ©Giulio Archinà

Fig. 4. Antonello da Messina, Annunciata, tempera and oil on panel, 45 x 34.5 cm., 1475-1476, Galleria Regionale della Sicilia di Palazzo Abatellis. ©Giulio Archinà

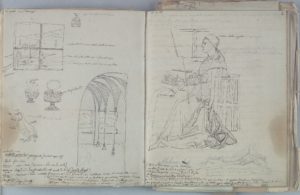

Despite the numerous themes of the exhibition, which have been already explored in other occasions, the Milan show really stands out for the display of nineteen drawings by Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle (1819-1897). Lent by the Venice Biblioteca Marciana, they lead visitors to discover Da Messina’s art. Cavalcaselle was the first art historian to trace the painter’s artistic journey and put his corpus of works together for the first time. After seeing the Saint Jerome in his Study in Thomas Baring’s London collection in 1854, Cavalcaselle copied the painting, carefully annotating its details and stylistic features, as can be seen in one of the drawings exhibited in the show (Fig. 6). With his uncanny eye, the Italian connoisseur detected the hand of Da Messina in the rendering of the saint’s drapery, leading the way to the correct attribution of the work to the pictore ceciliano, the Sicilian painter. Cavalcaselle recognised the coexistence of different stylistic features in the artist’s style. When copying the aforementioned Portrait of a Man (Fig. 5), he linked it to both Flemish art – to Hans Holbein and Van Eyck particularly – and Masaccio’s luminist research (Fig. 7). The aspect of some of da Messina’s works would have gone lost forever if Cavalcaselle would not have copied them carefully, as attested by some of the drawings on view in Milan.

Fig. 6. Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle, Saint Jerome in his Study, after Antonello da Messina, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice.

Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle, Portrait of a Man (cefalù), after Antonello da Messina, 30 x 21.1 cm., Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice.

Exhibited to the public for the first time, a document from the Milan Archivio di Stato shows that, in the 1470s, da Messina’s fame had spread all over the Peninsula. In 1476, via his secretary Cicco Simonetta, the Duke of Milan Galeazzo Maria Sforza offered da Messina the prestigious position of court painter. Sforza’s sudden death and the artist’s obligations in Venice prevented the latter from moving to Milan. More than five hundred years later, the Duke’s dream has eventually come true and Milan can finally enjoy the works of the non humanus pictor,2 the divine Antonello.

The exhibition Antonello da Messina is on view at the Royal Palace of Milan from February 21 to June 2, 2019.

1 Giorgio Vasari, “Life of Antonello da Messina,” in Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. 2 This definition comes from an inscription in the Madonna and Child executed by Antonello da Messina’s son Jacobello, where the latter describes himself as the son of a non-human painter: ‘Jacobus Anto.lli filiu no / humani pictoris me fecit.” The painting, which belongs to the collection of the Bergamo Accademia Carrara, is displayed at the end of the Milan exhibition.